Summary

- Many apps (social, browsers, games) request contact access even when it’s unnecessary.

- Allowing access lets apps upload and share your entire address book beyond your control.

- Contacts get sold, cross-referenced, and used for spam, scams, or building ghost profiles.

What do Pinterest, Microsoft Edge, TikTok, and Instagram have in common? They all try to access your contacts. In fact, many games and apps available on the Google Play Store request the same permission, even when they seemingly have no reason to. Here’s why you should be careful when granting this permission.

You would expect that only messaging and communication apps would ever request permission to access your contacts. However, pretty much every popular social media app wants permission to access your contacts. Pinterest, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and even LinkedIn want that data.

It’s not just social media either. Microsoft Edge, a phone browser, scrapes your contacts. PicsArt is a photo and video editor app with more than 1 billion downloads (easily the most popular utility of this kind), and it wants your contacts, too. Even games like Free Fire request access to your phonebook.

You almost never need to grant access to your contacts, unless it’s a messaging app like Telegram, Signal, or WhatsApp. Even in those cases, you can manually punch in the phone numbers without exposing your entire phonebook.

Most of the time, the reason these apps provide is just “app functionality” or something equally vague. Meta apps and TikTok explicitly state (on their Play Store pages) that they use the data for analytics, advertising, and marketing.

The pages don’t explain exactly how they do so, but the way it usually works is that these apps upload your contact lists to their servers to profile you and everyone in your contact list (more on that in a few).

For the end user, the only “feature” is contact-based suggestions. Basically, these apps will scan your contacts against their database of users and find people you might know. That might populate a “You May Know” following list or autofill suggestions in text forms.

Once you tap “Allow” on the “Allow access to contacts?” prompt, the app can instantly scan your entire address book. It can see names, phone numbers, associated email addresses, or other info you may have included when saving a contact.

From there, the app is free to do whatever it wants with that data. It can instantly upload all that information back to the server or constantly monitor your contact list for updates and sync changes in real-time.

That’s the problem with this particular Android permission, and what makes it so sensitive. There’s no way to reverse it, because even if you revoke it later, once the data leaves your device, it’s not in your control anymore. It can be copied, passed around, or stolen, so it can basically end up anywhere. You can’t delete the uploaded list once you’ve granted the permission, even if you uninstall the app.

It doesn’t end there. Apps can also request another related permission that allows them to read your call logs and metadata, who you’re calling, how often, when, and for how long are all recorded in the call logs. Thankfully, sensitive data like this isn’t easy to access. An app has to be made the default phone or Assistant app if it wants to access call records. Even so, there are apps like TrueCaller designed to replace those defaults, so call logs and metadata do routinely end up on third-party servers.

I already touched on this earlier when discussing why apps try to copy contact lists in the first place, but it goes beyond first-party use. The app that originally scraped the contact list isn’t the only one that can ever access it. They can sell that information to others. Data brokers trade, sell, and rent contact lists on the market.

The lists are cross-referenced with lists from other sources and linked with each other. Each contact, a node with a name, number, home address, or email address, can be a starting point for a rich profile. By aggregating other sources, these brokers can fill in gaps about location, job, demographic, and other personal data. Even a partial list could be filtered or grouped into meaningful segments.

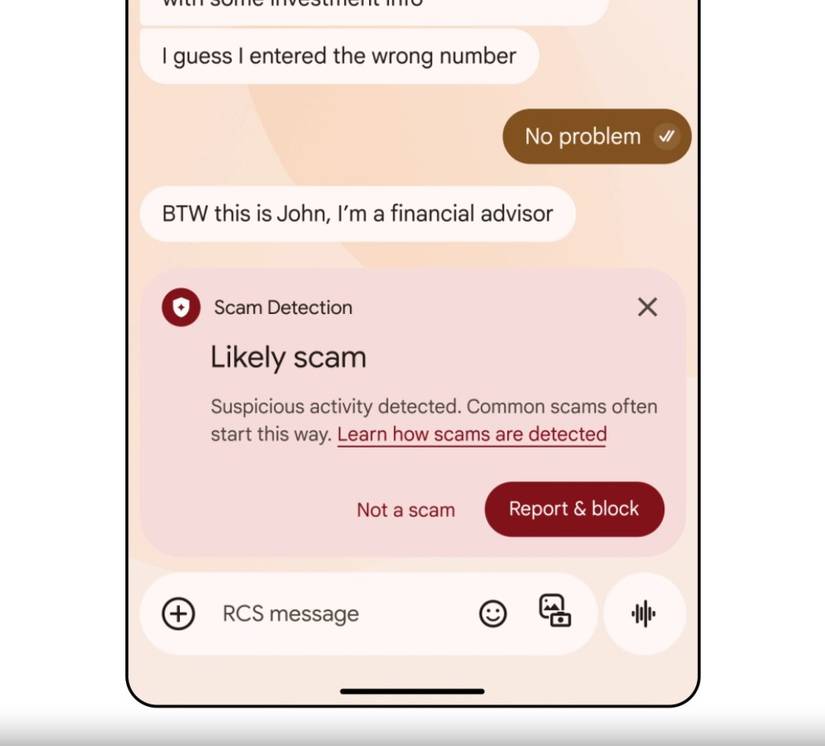

In a telemarketer’s hand, that list is now a tool to run a targeted ad campaign. Shady actors can use these contact lists to spam or scam people or create elaborate social engineering ploys.

Also, data breaches happen all the time. Billions of records (including names, phone numbers, and email addresses) are already floating around on the internet, and tech companies routinely suffer data leaks and breaches. Even giants like Meta and Apple aren’t safe.

Your Name and Phone Number are Likely in the Cloud (Even if You Never Shared them Online)

You can probably put this together yourself by now, but your personal info can end up in these places even if you didn’t personally upload it. All it takes is for someone to save your phone number or email address with your name and grant the contacts permission.

It’s how tech companies build “ghost” profiles on people. Even if you never signed up for a Facebook account, Meta likely still has a shadow account with your name, generated based on contact lists uploaded to the platform.

It’s also how anyone can look up your full name and other information with nothing but your phone number. Since your name likely appears on many contact lists, they can be cross-checked to verify your full name. Such databases, like TrueCaller, are conveniently available to anyone.

Whenever an app asks permission to access your contacts, remember that it’s not a harmless request. If possible, make it a point to never grant it, because you’re risking not just your privacy, but everyone who is on your contact list.