Corporations and the regulators that oversee them must do more to stop distracted driving by finally “bricking” the devices when their users are behind the wheel.

The National Transportation Safety Board recently called on federal regulators to develop new anti-distraction guidelines so that cell phone manufacturers, automakers, and other aftermarket companies that put diverting devices inside American cars have no excuse not to make “do not disturb while driving” modes default on all their products.

That recommendation was prompted by a grisly 2023 crash in which a 17-year-old Wisconsin driver who was texting behind the wheel struck and killed a 13-year-old Evelyn Gurney, an avid hockey player who was in the process of boarding her school bus.

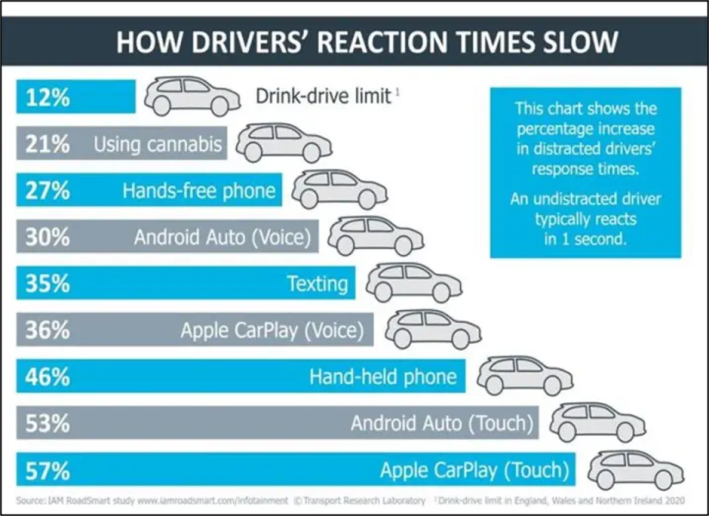

Virtually every cell phone has an in-motion “lock-out” mechanism that bars the driver from using its most distracting features, like calling, text messages, social media, and email apps, while still allowing limited access to navigation, music and emergency calls. Telematics companies that help insurers assess who deserves “safe driving” discounts — and whose apps are installed on countless phones — also brag that they can even sense whether a phone is being held by a driver or a passenger, based on minuscule differences in how people manipulate their devices whether they’re behind the wheel or just enjoying the ride.

Because lock-out tech isn’t always “on” by default, though, “only about 20 percent of surveyed cell phone users had the lock-out feature set to activate automatically when they drive,” according to a 2020 study Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

If regulators can enshrine those life-saving technologies into clear federal recommendations, though, it could be an important first step to making lock-out systems mandatory on all phones, not to mention dashboard “infotainment” screens and other aftermarket electronic devices that might take eyes off the road.

But the fight almost certainly won’t be easy.

The National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration did publish driver distraction guidelines back in 2013 — but those guidelines haven’t been updated since, even as Americans have become increasingly cognitively and socially enmeshed with their devices, according to NTSB’s Public Affairs Specialist Sarah Sulick.

Besides, such guidelines only talked about the visual and manual distractions of screens, not the cognitive “distraction hangover” that can linger for up to a minute after a motorist puts the phone down.

In the years since those guidelines were written, nine major cell phone manufacturers have shrugged off NTSB’s 2020 recommendation to voluntarily make “lock-out” mechanisms the default on all their devices. Instead, they’ve buried the button to enable “do not disturb while driving” mode under hard-to-find settings menus, failed to sync that mode with integrated dashboard devices, or made the feature easy for drivers to disable with a single swipe.

Apple even claimed that “there is not a reliable way to determine that the device is being used by the vehicle’s driver and not a passenger” — even though that technology has existed for years and comes standard on many insurance apps in the Apple app store.

“There has been so much change in technology and our personal electronic devices since those first guidelines came out,” Sulick said. “There’s really an opportunity for NHTSA to update those guidelines based on the technologies that we have today.”

Some advocates might argue that it’s past time to update America’s distraction guidelines based on the sheer scale of the carnage that screens are causing today — and how unlikely that carnage is to abate on its own.

According to NHTSA studies cited by the NTSB, an estimated 6.4 percent of drivers were actively using their devices during daylight hours in 2022, and phones were identified as a distracting factor in a stunning 64,979 crashes in 2023.

And because police don’t always subpoena cell records after crashes — and NTSB itself only investigates a tiny fraction of roadway tragedies — those numbers are almost certainly a significant undercount, and give U.S. residents the false impression that it’s okay to take the occasional call on the road.

“People don’t truly understand the risks,” added Sulick. “I also think it’s challenging to determine that distraction was causal in a crash. We have so many fatalities on our roadways; there are so many other factors that are also involved that sometimes, it can be hard to choose which ones to focus on.”

Of course, mandating lockout mechanisms isn’t the only thing America can do to combat the distracted driving epidemic.

The NTSB notes that only 31 states currently prohibit drivers from holdingcell phones behind the wheel — and none bans all cell phone use, unless drivers are very young or operating a school bus. Strengthening those laws and complementing them with educational campaigns could encourage some Americans to pay more attention to the driving task, even if others will require stronger interventions.

And if nothing else, when it comes to teenagers like the one who killed Evelyn Gurney, Sulick hopes parents step up and urge their kids to pay attention.

“Younger people are used to being passengers and using their cell phones for entertainment as a passenger in a vehicle,” she added. “But when they transition to being the driver, they have the responsibility of this vehicle — and they must put the cell phone down.”