- Universal Health Coverage (UHC) means everyone can access healthcare without financial hardship, but progress towards achieving this has stalled.

- The latest research on achieving UHC also focuses on the need for health equity, which is when everyone can attain their full health and wellbeing potential.

- This will require a willingness by healthcare leaders to collaborate with both public and private sector organizations on research and funding.

After nearly a decade of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and despite much progress, efforts to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) have “largely stalled” according to the World Bank.

UHC is when everyone can access the healthcare they need without suffering financially. But some 4.5 billion people still lack sufficient coverage and the share of households using more than 10% of their budget for out-of-pocket healthcare payments has increased since 2015. What’s more, up to 1.3 billion people have been pushed further into poverty as a result of medical spending since the pandemic.

On International UHC Day, 12 December 2024, we must remind ourselves that the job of achieving UHC is far from finished.

COVID’s lasting impact on healthcare funding

UHC is as much a financing mechanism as it is a lever for healthcare delivery. Government expenditure on healthcare, such as the proportion of GDP allocated to the sector, is often a key consideration for a country’s UHC strategy. Since the pandemic, government spending on healthcare has actually been increasing and is projected to sustain that growth, rather than fall. Annual growth rates are projected to normalize to about 5% by 2030, driven by increases in demand as well as broader inflationary trends. The fastest area of spending growth is in prevention.

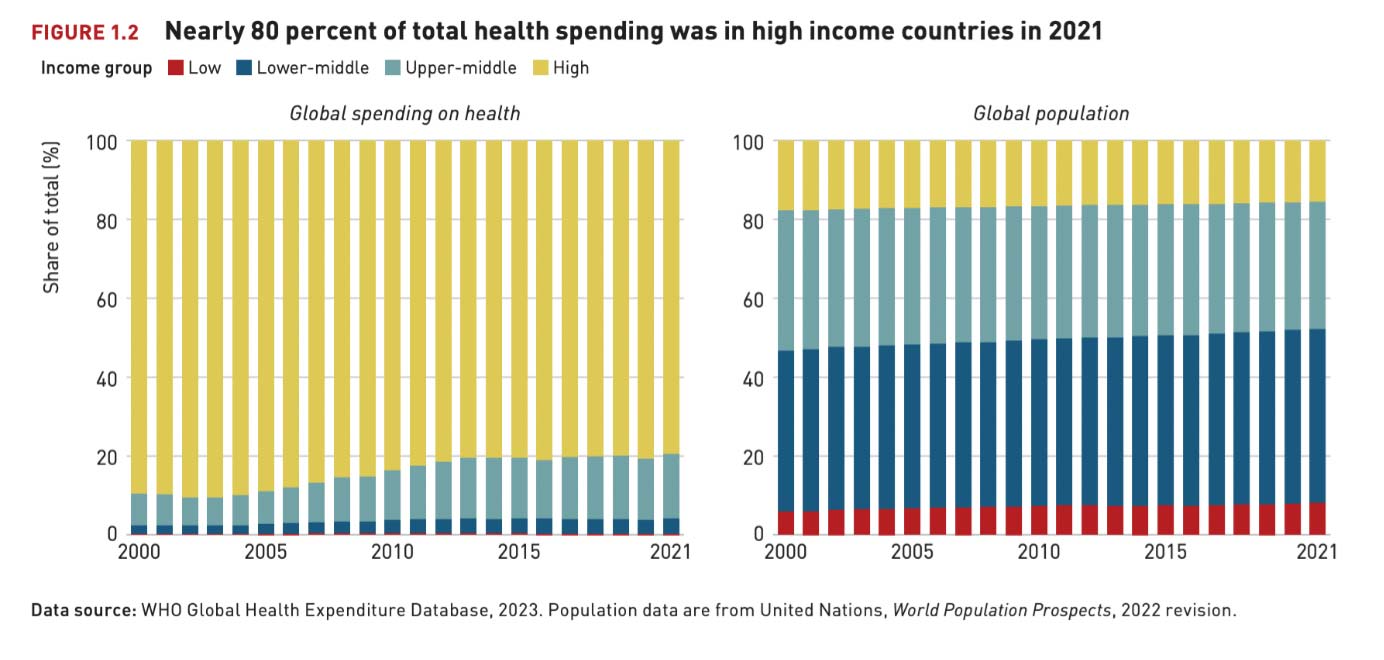

But the challenge lies in allocating these resources more equitably. Per capita healthcare spending can vary significantly between countries. High-income countries, representing 16% of the world’s population, account for more than three quarters of healthcare expenditure, for example.

Most governments urgently need to transform public sector finance in the face of deteriorating economic conditions, rising inflation and legacy debt-servicing obligations. Three in four claim this will happen in the next decade and could involve alternative funding sources such as a universal basic income or more private sector finance. Achieving the SDGs, including more equitable UHC, will rely heavily on the capacity and capability of such financing decisions.

A new health equity agenda

It is perhaps for these reasons that the progress on UHC made within the last decade, while admirable, may not be sufficient to deliver on the SDG promise over the next decade. This premise was the inspiration behind a 2021 World Economic Forum report and subsequent research into “UHC 2.0”.

Changing demographics over a generation means UHC 1.0 may now be unsustainable, according to this research: populations have tripled in many countries and increased by a factor of 10 in lower middle-income countries (LMICs), the world’s median age has increased by 40% and while the infectious disease burden has dropped by 50%, chronic disease contributes to 500 million years of life lost annually.

In addition to all of this, the job of achieving UHC remains unfinished. Less than half of the global population has access to essential healthcare services, 80% of deaths occurring in children under age five are in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, and LMIC tax-to-GDP ratios are half of the target when 70% of people informally employed.

Indeed, this research indicates modern “design slippage” by countries attempting to implement UHC 1.0. The result is undesirable resourcing trade-offs that do not deliver on the promise of health-for-all – especially in the face of frequent health system shocks and crises, such as the COVID pandemic.

This UHC 2.0 research includes recent case study analysis from Nigeria on maternal health and Indonesia on telemedicine, as well as building on prior research about immunization, diabetes and rare diseases. It shows that public and private sector stakeholders alike are well aware of the existing UHC constraints. But they are also increasingly concerned that these constraints could create uneven “cultures of free expectations”, as well as a “missing middle” in socioeconomic development terms. UHC 1.0 limitations tend to force stakeholders to apply near-term break-fix controls, such as limiting the scope of coverage even as they seek more innovative solutions for their populations.

Enter an upgraded agenda for UHC and SDGs: “health equity”. This is “achieved when everyone can attain their full potential for health and wellbeing”, according to the World Health Organization.

How to create health equity

UHC 2.0 research outcomes describe a strong foundation for health equity. It shows that stakeholders want to adopt forward-looking health financing concepts such as mandatory UHC contributions, online-offline care models (with data as a critical source of value), smarter procurement, privatized national health insurance, better financial quantification of future healthcare workforce needs and, more generally, efficient use of available resources.

Image: Christopher Hardesty, 2024

Near-term strategies for health equity could involve countries testing out alternative UHC concepts among existing sites and use cases and publicizing those concepts within their own borders, as well as to other countries with similar attributes. These countries could then gather evidence to inform future supernational healthcare policy.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for Health and Healthcare champions UHC on a global scale by advocating, advancing and driving action across all health domains. By engaging stakeholders from governments, the private sector, the UN, civil society and academia, the centre aims to accelerate progress toward achieving UHC.

Fully implementing a version of UHC 2.0 that prioritizes health equity will require a thoughtful, stepwise revolution to help healthcare leaders make decisions, while also bearing in mind cultural appropriateness. Healthcare leaders in all countries should ensure stability, continuity and an open-minded attitude to public-private collaboration in order to usher in a new generation of equitable health and care financing for people around the world.