Although the Premier League has never generated so much money, the fact remains that profitability continues to be a struggle for most clubs. One of the consequences is ever increasing levels of debt.

Of course, there are many reasons why a football club would take on debt, including investment in infrastructure, spending to improve the squad, covering operating losses and even as a pre-cursor to investors taking a stake in the club.

Covering losses was a particularly important factor during the COVID pandemic, as clubs had to tap into the capital markets or rely on the benevolence of their owners to compensate for huge revenue losses arising from playing games behind closed doors.

There is also a degree of tax efficiency behind a decision to opt for debt financing, as opposed to equity injections, because interest on loans is tax deductible (unlike dividends).

However, there are clearly some disadvantages associated with the explosion of debt, as highlighted by the government’s white paper, “A Sustainable Future – Reforming Club Football Governance”.

Before we start exploring the growth in debt in detail, we should clarify exactly what we are talking about, as there are so many different definitions.

At the narrowest extreme, we have just bank debt, but the broadest extreme covers total liabilities, which includes all financial obligations, including transfer debt, staff payables, tax liabilities, trade creditors, provisions, accrued expenses and even deferred income.

The net debt reported in an English club’s financial statement is in line with IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) and essentially covers purely financial obligations, such as overdrafts, bank loans, bonds, shareholder loans and finance leases less cash.

For the purpose of this review I will take the 2023/24 audited accounts of those clubs playing in the Premier League that season.

After many years when Premier League debt levels were relatively flat, this has really taken off in the last few years, rising from £3.2 bln in 2017 to a high of £5.2 bln in 2020.

This then dropped to “only” £4.0 bln in 2021/22, but the decrease was a bit misleading, as it was only due to Chelsea writing-off £1.5 bln of debt following Roman Abramovich’s forced sale of the club.

Since that large once-off transaction, gross debt has increased by around £700m (17%) to £4.7 bln.

If we exclude Chelsea from the calculation, thus removing the substantial distorting factor of their £1.5 bln write-off, the steady growth in Premier League debt becomes more evident.

On this underlying basis, debt in England’s top flight has more than doubled in the last seven years and has never been higher.

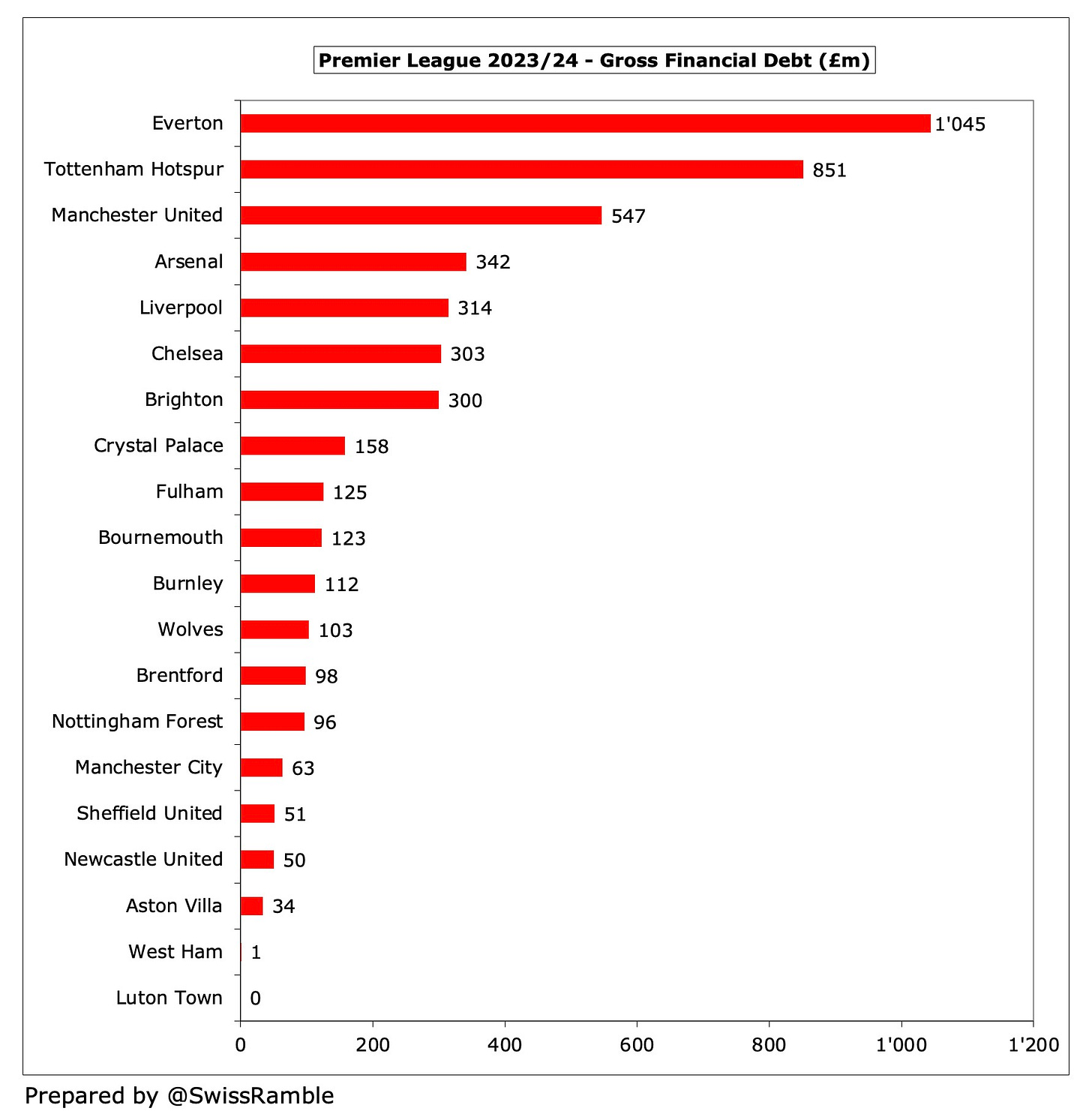

Over half of the debt is at just three clubs, namely Everton £1.0 bln (new stadium and squad investment), Tottenham £851m (new stadium) and Manchester United £547m (the lingering effects of the Glazers’ leveraged buyout).

In addition, four other clubs owe more than £300m (Arsenal £342m, Liverpool £314m, Chelsea £303m and Brighton £300m).

On the other hand, Luton Town and West Ham were essentially debt-free.

Gross debt is offset by large cash balances in some cases, but the total cash held in the Premier League fell £207m (29%) from £724m to £517m in 2024, which was less than half of the £1.1 bln peak in 2020, when many clubs took out large loans to cope with COVID shortfalls.

![English football YouTuber Mark Goldbridge [Photo = Yonhap News]](https://koala-by.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/news-p.v1.20250821.6f2e3963c24e47e08cd31c0cff850891_P1.png)