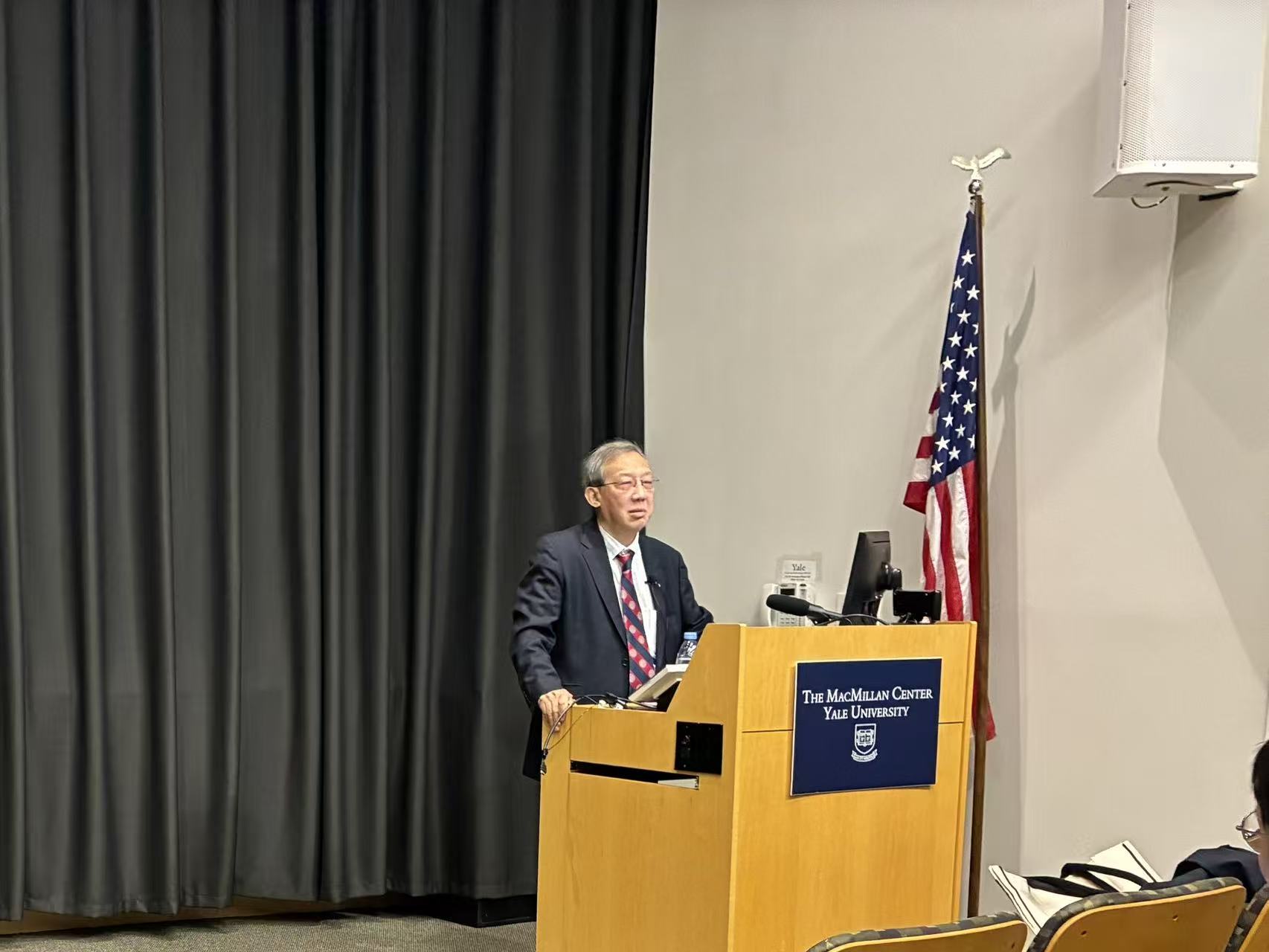

A historian delivered a lecture on Zhou Enlai, one of the founding leaders of the People’s Republic of China.

Gillian Peihe Feng

Contributing Reporter

Gillian Peihe Feng, Contributing Photographer

The Council on East Asian Studies, a part of Yale’s MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies, hosted an annual lecture on Chinese studies on Thursday afternoon.

The lecture, titled “Zhou Enlai and China’s ‘Age of Revolutions,’” was delivered by Chen Jian, a history professor at New York University and NYU-Shanghai. Chen’s academic biography of Zhou Enlai was published by Harvard University Press in 2024.

Zhou Enlai was one of the most important figures in the Chinese Communist Party. As the first Premier and Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic of China, Zhou played a central role in shaping the country’s early domestic and foreign policies — including the Cultural Revolution and the normalization of the U.S.-China relationship in the 1970s.

In an email to the News, Kathy Rupp, the director of the Council on East Asian Studies, spoke about the importance of the Hume Lectures, and its namesake, Edward H. Hume ’1897. According to Rupp, the Hume lectureship aims to bring prominent scholars in the field of East Asian studies to Yale.

“More recently, the Hume lecture has focused solely on China,” Rupp wrote. “It is our hope that Yale students and other members of the Yale community will learn more about this very important area of the world.”

Chen was introduced by Arne Westad, a history professor at Yale. Westad praised the expansiveness and rigor of Chen’s scholarship on modern Chinese and international history.

“There are very few people who had the kind of impact that he has had on the writing of Chinese history and international history in his generation,” Westad said. “It’s quite unique to have someone who has made so many contributions in different directions.”

Chen began his lecture with a contemplation on its title — most specifically, the use of “revolutions” instead of the word’s singular form. According to Chen, 20th century China was characterized by a series of revolutions: from the 1911 revolution to the Cultural Revolution.

“The subject of my talk today, Zhou Enlai, was involved in almost every phase of this age,” Chen said.

Chen’s lecture focused on Zhou’s alignment and dissension with Mao Zedong, the founder of People’s Republic of China. Instead of following previous scholarships, which portrays Zhou as the “accomplice” of Mao and “almost a villain,” Chen understands Zhou’s political stance to be much more complex.

“Certainly he was not a Maoist, certainly not an internalized Maoist,” Chen said.

Drawing evidence from his archival research, Chen traced Zhou’s involvements in the revolutions of 20th-century China. According to Chen, Zhou was central in devising the Chinese Communist Party’s “grand strategy” that led to their victory over the Nationalist Party in the Civil War, which included fashioning themselves as democratic.

Chen argued that Zhou “hoped” to sustain democracy after the CCP became the ruling party of China and tried to exert a moderating power over the party. His attempts were consistently suppressed by Mao, who “controlled the party with absolute power,” Chen said.

“He tried very, very hard to serve as a good premier,” Chen said. “This caused him to become a Mao enabler.”

Chen talked about Zhou’s legacy on China’s foreign policy. Chen recalled having “a two hour exchange with Kissinger here at Yale,” referring to a conversation he had with Henry Kissinger about Zhou. According to Chen, when Kissinger visited China in 1973, he had a confidential meeting with Zhou. Chen said Kissinger offered China assistance in the case of a Soviet missile attack, to which Zhou neither agreed or denied.

Chen ended his lecture with a personal anecdote which recognized Zhou’s complexity.

“When I was writing Zhou Enlai biography, people often asked me, including my 90-year-old father when he was still alive. ‘Chen Jian, tell me, is Zhou a good guy or bad guy? Yes or no?’” Chen recalled. “No, I cannot answer this question.”

Jamin Nuland ’27 described Chen as “a great storyteller.”

“He creates an ambiguous tale of Zhou Enlai’s position, while people tend to often see the CCP as, you know, a unified stance,” Nuland said. He added that it is “great” to see a more “complex” story.

Aiken Wang ’27 said the lecture was a “unique chance to learn more about Chinese history and Zhou Enlai” because classes on this topic at Yale are limited.

“I appreciate the more academic work in assessing who Zhou Enlai was,” Wang said.

The MacMillan Center is located on 34 Hillhouse Avenue.