The pictures are heartbreaking: convoys of United Nations-marked trucks inching toward bomb-scarred cities, desperate children clamoring for supplies. These images seem to prove that the international system is, at the very least, trying to help. Yet in every conflict I have studied—Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Ethiopia and Gaza—the same trucks double as cash machines for warlords, militias and authoritarian regimes. Aid diversion is a widespread problem in humanitarian operations. Unless the U.S. and other donors rewrite the rules so that aid can’t be separated from accountability, they will keep subsidizing the conflicts they abhor.

Somalia shows how thoroughly diversion can be built into routine. Three clan cartels win most World Food Program transport contracts, skim 30% to 50% of the cargo, and then split the spoils with those who transport the food and those who control the displacement camps. Based on U.N. reports and monitors, my coauthor and I estimate in our study that barely one-eighth of donated food reaches intended households.

In Syria, former President Bashar al-Assad insisted that all aid be converted at a government-set rate to roughly half the market price, enabling the regime to pocket at least $60 million in 2020 alone, while blocking aid from reaching the opposition by designating it as “unsafe.”

In Ethiopia, U.S. Agency for International Development workers discovered that their implementing partner, the U.N.’s World Food Program, was aware of industrial-scale theft by the Ethiopian military but failed to stop it. Large quantities of wheat were diverted to private mills to make flour for the army.

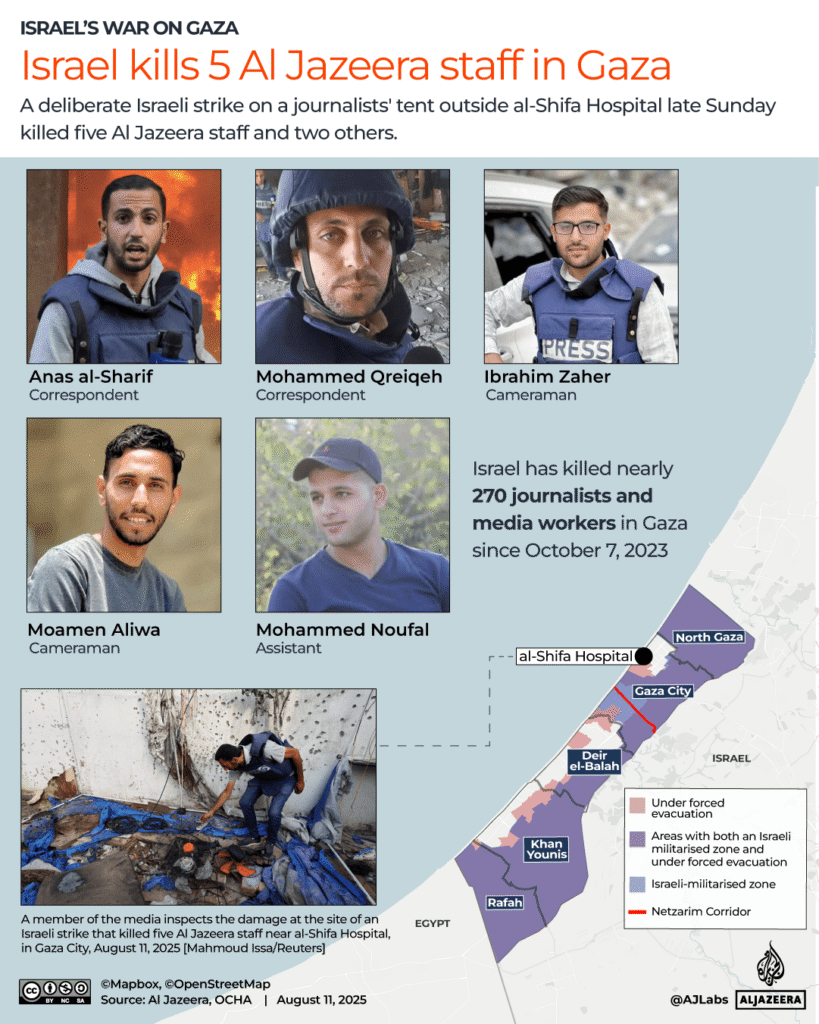

Gaza presents the longest-running case of diverted aid. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency, with a $2.48 billion annual budget in 2024 and 13,000 local staff, effectively provides most public services in Gaza. That frees Hamas to use its resources for tunnels and rockets. In regions under its control, it taxes incoming aid and places loyalists on the payroll. A donor freeze after evidence that Unrwa personnel joined the Oct. 7, 2023, attack lasted only months; services resumed with no vetting reforms because, donors said, “there is no alternative.”

Diversion persists for several reasons. First, the moral considerations are difficult: When officials weigh “people will die tomorrow” against “fighters will grow stronger next month,” tomorrow always wins. Second, people give priority to institutional survival: The humanitarian sector employs some 570,000 people and until 2025 spent about $35 billion a year, and agencies that refuse armed groups’ terms lose access, budgets and jobs. Third, adversaries are able to adapt: Warlords remain in place while aid workers rotate; they open businesses posing as nongovernmental organizations and bill the U.N. for delivering cargo. Add fear of donor backlash and the result is a continuing lack of accountability. Those who break the rules hold more leverage than those sworn to enforce them.

But accountability is still within reach if donors step up and put pressure on humanitarian organizations. When donors finally cut funds because they find the scale of diversions unacceptable, even hard-line actors bend. When Washington paused food aid to Ethiopia in 2023, diversion plunged, and the government grudgingly accepted QR-coded tracking.

The U.S., the European Union and Gulf states combined supply more than 70% of global humanitarian budgets. Together, they could enforce five conditions on every grantee:

• Require nondiversion benchmarks. All access fees, escorts and local taxes must be disclosed in advance; one missed benchmark triggers a 12-month funding pause.

• Integrate security. Grantees may hire donor-vetted guards or accept U.N. peacekeeper escorts; private deals with militias void the grant.

• Build in insurance for whistle-blowers. Two percent of every grant pays for external audits and the legal defense of whistle-blowers.

• Create sunset clauses. Missions longer than 10 years shut down unless donors unanimously extend them after a public review.

• Fund innovation. Create dedicated funding streams for fintech tracking, QR-coded commodities and other tools that make diversion more difficult.

None of this requires rewriting international law. It’s simply about enabling donors to use the one lever they control: money. Every diverted dollar undermines U.S. counterterrorism goals, fuels migration pressure on Europe, and forces Gulf monarchies to spend twice—first on aid, then on arms. Conditional funding flips those incentives. Regimes that want to look legitimate on the global stage must choose: guns or food, not both. Boosting accountability would also blunt the common critique that Washington preaches good governance while financing bad actors through humanitarian back doors.

Critics say pausing aid is immoral, as civilians would starve. This risk is real but not as definite as how it is often presented. Typically, there isn’t enough data to infer the effect that a pause will have. The June 2023 Ethiopia pause triggered dire warnings of widespread famine. While some people no doubt suffered, the warnings didn’t materialize. Acute food insecurity and child malnutrition went down in 2023 compared with 2022. In Yemen, food-security analyses during the suspension were limited to southern Yemen, where the pause in aid didn’t occur. Acute food insecurity did rise in these areas, which were unaffected by the halt but where multiple other forces were at work: currency collapse, wage arrears, siege tactics.

Against the immediate risk of human suffering, donors must consider that allowing aid diversion could extend that risk for years. A cross-country analysis of 621 leaders in 123 countries from 1960 to 1999 showed that large, unconditional aid inflows help autocrats survive. World Bank data show that unconditional aid correlates with higher corruption and weaker rule of law.

Nothing obligates donors to bankroll the fighters causing the suffering. Setting conditions on aid to prevent diversion aligns humanitarian spending with humanitarian intent.

Climate shocks, urban sieges and pricier grain will likely push humanitarian budgets beyond $50 billion within a decade. Without reform, much of that money will feed armies before children. Worse, each scandal makes future interventions politically toxic, putting civilians in real need at risk of not receiving help. The choice is stark: tighten the taps now or watch the well run dry.

Ms. Barak-Corren is a law professor and the Haim H. Cohn Chair in Human Rights at Hebrew University of Jerusalem.