China has stepped up its push for artificial intelligence dominance by doling out subsidies for data centres and linking underused processors across the country via homegrown technology.

The country is spending billions — and converting rice fields into massive server farms — to establish clusters of data centres to meet the increasing demand for AI, according to a Financial Times report.

One such “mega-cluster”, being developed in the eastern city of Wuhu, has seen investments worth $37 billion from 15 companies, the report said.

Also on AF: Alibaba Shares Jump on Data Centre, AI Plans and the Ma Factor

It has also benefitted from generous local government subsidies that potentially cover up to 30% of AI chip procurement costs, it added.

The report quoted one of the project’s suppliers as saying the project was set to be “the Stargate of China” — a reference to OpenAI and SoftBank’s project to expand the United States’ AI infrastructure.

But clusters like the one in Wuhu are only one part of China’s plan.

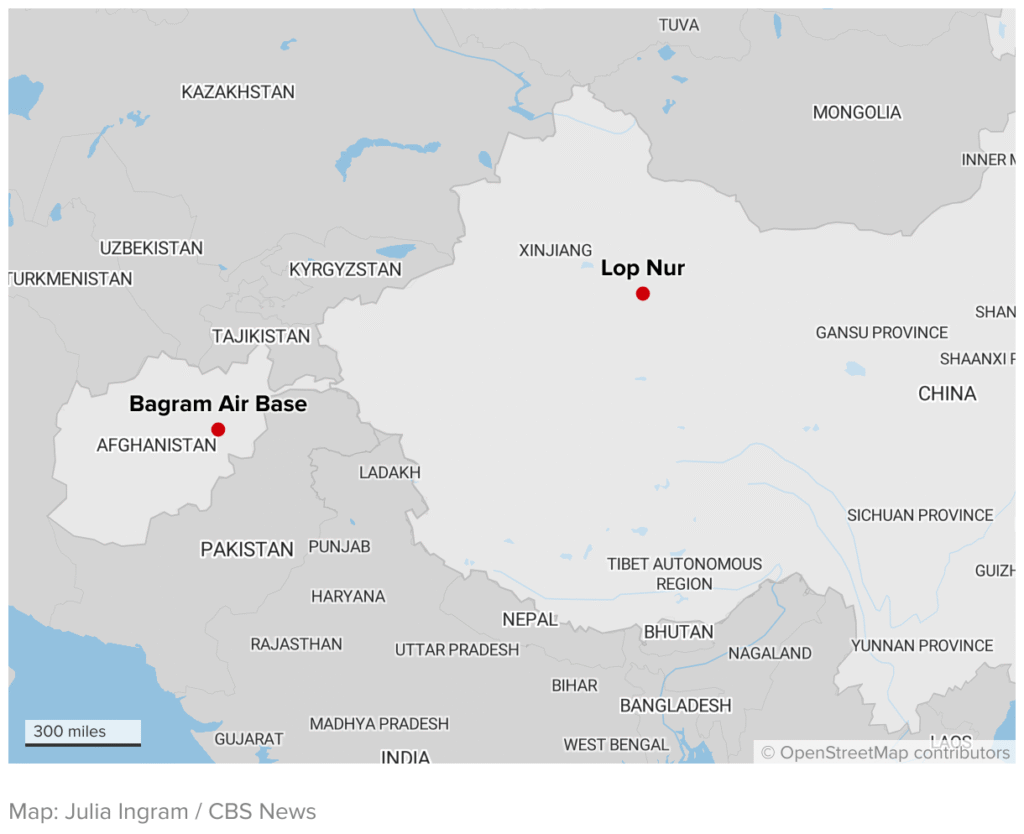

The other involves utilising existing data centres in remote regions in the west to train large language models and linking them to eastern hubs — such as the one in Wuhu — that are well-positioned to meet AI demand from economic hubs like Shanghai and Beijing.

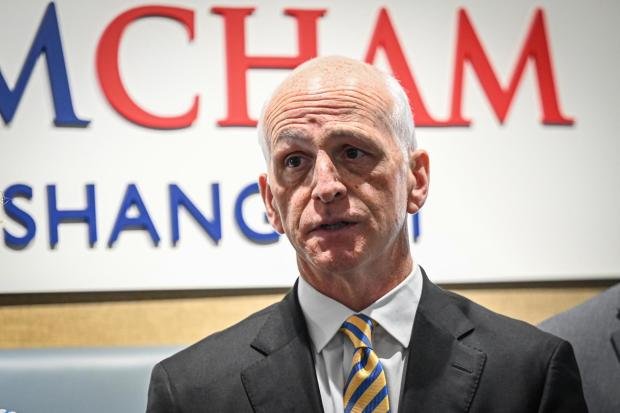

The strategic plan points to Beijing’s effort to “triage scarce compute for maximum economic output,” Ryan Fedasiuk, a former State Department adviser on China, told the FT.

“Beijing is now planning data centre infrastructure with this in mind,” he added.

‘Eastern data, Western computing’

News of Beijing’s plan to link clusters of data centres from across the country comes at a time when the country is tackling a massive glut of AI computing power, alongside a shortage of the advanced processors necessary to run critical AI tasks.

As of July this year, China was using only 30% of its intelligent computing capacity. A key reason behind that was “blind investment” from local governments since 2022 into computing centres built in remote provinces, where a lack of technical expertise and consumer demand left much of their computing power idle.

Meanwhile, China also needs centres positioned closer to its main hubs that actually drive demand. These centres need to be adept at running AI inference — the process that allows large language models to use their existing data to make predictions or decisions in response to a user query. Running AI inference requires specialised AI chips, supplies of which remain limited amid Washington’s export curbs on China.

By linking remote data centres with new hubs along key cities, Beijing is looking to deal with both those problems.

Last year, Chinese state media reported that by the end of June 2024, Beijing had invested more than 43.5 billion yuan ($6.12 billion) to build eight computing hubs as part of a ‘mega data project’ dubbed “Eastern data, Western computing”.

Launched in 2022, the project is designed to develop the capacity of inland regions in the west to store and process data transmitted from economically advanced areas. Doing so would allow China to tap into the abundant energy resources in the west and transfer computing power to the east.

The project would also involve the development of 10 national data centre clusters, state media reported, citing National Data Administration chief Liu Liehong. Liu added that the project had received total investments of more than 200 billion yuan ($28 billion) at the time.

Meanwhile, Reuters reported in July that state investment has continued to surge for data centres used in computing, with 24.7 billion yuan ($3.4 billion) in funding last year and another 12.4 billion yuan in the first half of this year.

Black market and homegrown tech

Still, all that funding pales in comparison to the $500 billion that the Donald Trump administration earmarked for the Stargate project this year. Early this week, chipmaker Nvidia — the world’s most valuable firm — also announced plans to invest up to $100 billion in OpenAI and supply data centre chips that will ostensibly be deployed in the Stargate project.

Chinese AI data centres, meanwhile, have had to depend on less powerful processors or tap into the black market to put together advanced hardware. Some suppliers have also secured data centre servers that use Nvidia’s advanced Blackwell chips that are banned from being exported to China, according to the FT report.

But key to the Chinese project is the ‘link’ between the hubs in the east and west.

To do so, Beijing has directed its firms China Telecom and Huawei to use their networking technology to link processors across multiple sites into a centralised computing cluster, according to the FT.

The technology is not new. It is also not efficient. But Chinese tech giant Huawei is reportedly working on fixing that with continuing work on a new ‘UB-Mesh’ technology that is designed to unify all interconnections across AI data centres. Huawei said last month that while the technology is fraught with challenges, it can cut costs and time lags, and improve the training efficiency of LLMs.

And like most recent Chinese breakthroughs in AI, Huawei has also committed to making the technology open-source.

Cutting foreign dependence

Huawei’s technology could be key to Beijing’s larger plan of setting up a national, state-run cloud service that could harness all of the country’s surplus computing power.

According to the July report from Reuters, Beijing is aiming to develop a standardised interconnection of public computing power nationwide by 2028. Aside from supporting its AI ambitions, Beijing aims to use the network to manage its computing glut by creating a platform to sell excess computing power.

But Huawei’s plans serve another key purpose for Beijing — cutting China’s reliance on Western technology.

China’s chipmakers, in particular, are rushing to reduce the country’s dependence on Nvidia and aim to triple their AI chip output by next year.

Last week, state media reported China Unicom was using these homemade AI chips to power a $390-million data centre in Xining, the capital of the western province of Qinghai. The state-run telecom giant had so far used 23,000 domestically made AI chips, state broadcaster CCTV said.

Alibaba’s chip unit T-Head supplied about 72% of those chips, with the rest coming from other domestic firms. The report also said a newly developed Alibaba chip positioned it as a close competitor to Nvidia’s H20 chip.

That same day, the Financial Times reported that China’s internet regulator had banned top tech firms from buying Nvidia’s AI chips.

Also read:

Huang Voices Disappointment After China Bans Nvidia’s AI Chips

Nvidia’s Latest AI Chip For China Finds Few Takers

China Targets US Chip Sector With Probes Into Nvidia, ‘Dumping’

Chinese Tech Giants ‘Want Nvidia Chips’ Despite Beijing Pushback

Nvidia CEO Says US Export Curbs on AI Chips is ‘Flawed’ Policy

Chinese AI Firms, Chipmakers Form Alliance To Ditch Foreign Tech

China’s Huawei ‘Hoping Its New AI Chip Can Outpower Nvidia’

China’s Huawei, SMIC ‘to Ramp Up Production’ of Newest AI Chip

Satellite Images Show Huawei’s Expanding Chip Facilities – FT

DeepSeek Cut US-China AI Gap to Three Months, AI Expert Says

Nvidia’s Bid To Stop Huawei

China Science Vs US Export Controls

Vishakha Saxena

Vishakha Saxena is the Multimedia and Social Media Editor at Asia Financial. She has worked as a digital journalist since 2013, and is an experienced writer and multimedia producer. As a trader and investor, she is keenly interested in new economy, emerging markets and the intersections of finance and society. You can write to her at [email protected]