The Board of Legends deliberated. Opinions were swapped, cases made, and gradually 100 names became 25.

Its eclectic members were tasked with deciding the winner of the 2025 Golden Boy, the best under-21 player in European football. Each brought their own experience. Among them were Ballon d’Or winners Andriy Shevchenko, Pavel Nedved and Hristo Stoichkov. There were past Golden Boys, including Cesc Fabregas, and even a member of the Swarovski dynasty. Who better, perhaps, to spot a diamond?

Through the windows of the Sala Trasparenza in Turin’s tallest building, the Piedmont Region Headquarters, the snow-capped Alps were visible on this sunny winter’s day. The winner came from the other side of them. Helping the ”Board of Legends’ come to a decision was a selection of Europe’s media outlets, including The Athletic. With Barcelona’s Lamine Yamal ineligible — Tuttosport, the Turin-based sports daily newspaper and organisers of the Golden Boy, decrees that former winners cannot win it again — they settled on Desire Doue of Paris Saint-Germain as the latest recipient.

Doue wasn’t the only PSG affiliate to pick up a prize. Nasser Al-Khelaifi was named best president and his recruiter-in-chief, Luis Campos, the best football executive, ample recognition for the pivot from a superstar model to one based around a group of Golden Boys that culminated in PSG winning the Champions League for the first time last season.

Doue’s team-mates Warren Zaire-Emery and Senny Mayulu were on the shortlist, too. Neither of them was man of the match in the final in Munich, though, where Doue did more to demolish Inter than anyone. Inter’s former player, the Frenchman Benoit Cauet, spoilered Doue’s victory by saying France coach Didier Deschamps would be very happy with the outcome of the Golden Boy.

Cauet was invited by Tuttosport to opine on why France — and particularly the Paris area — continues to produce talent at a rate Italy and nobody else can match. Only one Italian has won it since the founder of the Golden Boy, Massimo Franchi, suggested Tuttosport launch the award. That was Mario Balotelli, 15 years ago.

Mario Balotelli was the last Golden Boy winner from Italy (Claudio Villa/Getty Images)

Two Italians were nominated this time. Inter striker Pio Esposito and Liverpool centre-back Giovanni Leoni were wildcards. “There were actually two and a half,” Franchi joked. He was counting Real Madrid’s Franco Mastantuono, too, since the Argentinian could complete his move from River Plate thanks to his Italian passport and ancestors from Potenza.

France and England, by contrast, had five candidates each. Why can’t Italy develop more? Juventus, who take up the most pages in Tuttosport, are a case in point. When the national team failed to qualify for the 2018 World Cup in Russia, they were the only club to take the opportunity to enrol a B team in Italy’s third division. The idea was to expose academy kids to men’s football earlier and bridge the gap between youth and senior football.

It has been a big success. ‘Juventus Next Gen’ has supplied the senior side with several first-team regulars. A couple of them even made this year’s Golden Boy shortlist, allowing Tuttosport’s editor Guido Vaciago to counter a comment from the president of the Piedmont region, Alberto Cirio, that Juventus players never win the award. On the contrary — Paul Pogba won it in 2013. Juventus bought Matthijs de Ligt in 2018, and now Next Gen graduates Kenan Yildiz and Dean Huijsen were at least on the 25-man roll call.

But Yildiz (now a Turkey international) and Huijsen (Spain) were recruited from Bayern Munich and Malaga when they were super young. Huijsen, who Juventus sold too soon and for too little, is illustrative of another phenomenon. The Golden Boy shows the fertility of French football but also highlights the gravitational pull of the Premier League, the richest of all.

Nine Golden Boy candidates play in England. Huijsen, now at Real Madrid, left Juventus for Bournemouth. Jorrel Hato and Estevao moved to Chelsea from Ajax and Palmeiras. Geovany Quenda, listed as a Sporting player, will follow them to Stamford Bridge at the end of the season. Lucas Bergvall joined Tottenham from Djurgardens.

Dean Huijsen was on the books at Juventus but has left Italian football behind him (Denis Doyle/Getty Images)

The picture painted of Italian football is a diptych: half about Italians not coming through, half about the financial temptation to sell foreign prospects early, as most clubs act from a position of economic weakness vis-a-vis the Premier League.

It is, however, a portrait that does not tell the whole story. Italy won the European Under-19 Championship in 2023. The goalscorer in the final against Switzerland, Michael Kayode — ex-Fiorentina, now at Brentford — has been the talk of the Premier League this season (for more than his long throws). Italy then won the Under-17 Euros in 2024.

Player of the tournament Francesco Camarda had already, at 15, become the youngest Serie A debutant in history. On loan at Lecce from Milan, he is seen, along with Inter’s Esposito, as having the potential to one day end Italy’s belated wait for a No 9 in the mould of the greats from years gone by.

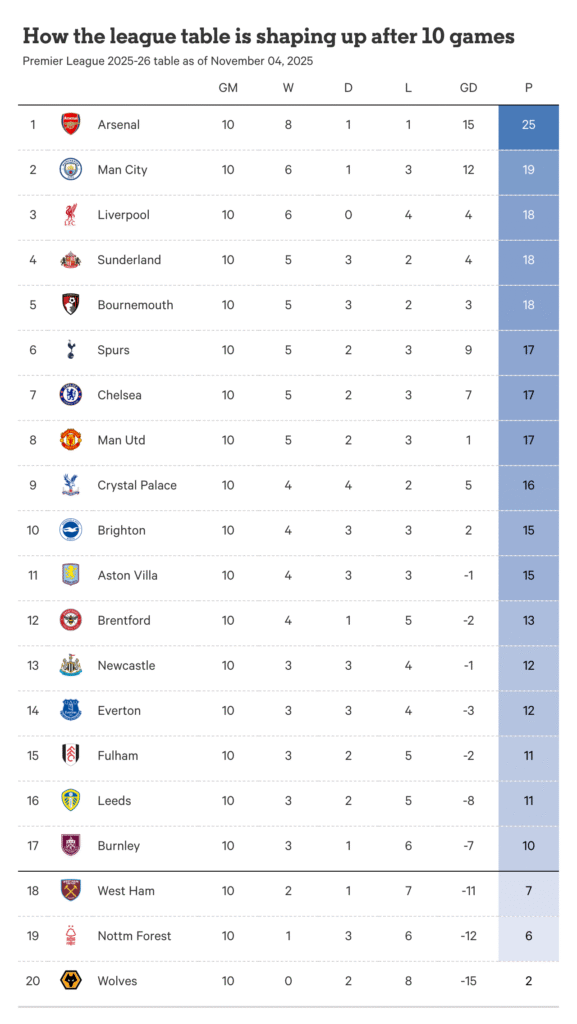

It’s not that Italy is completely lacking talent. Gianluigi Donnarumma perhaps would have won the Golden Boy award if goalkeepers were less regularly overlooked for individual awards. Italy’s captain, a treble winner with PSG last season, is now Manchester City’s No 1. Riccardo Calafiori is playing a major role in Arsenal’s title push. Newcastle United’s Sandro Tonali is the best midfielder in England, according to the former Manchester United playmaker Paul Scholes. Premier League clubs like up-and-coming Italian centre-backs, too.

After Brighton bought Diego Coppola, Liverpool moved for Leoni. What Italy lacks is the great No 10s of old — Francesco Totti, Roberto Baggio, and Alessandro Del Piero. They lack depth, too, and confidence, which was understandably shaken by missing back-to-back World Cups. Few remember Italy winning Euro 2020 in between.

Among Europe’s top five leagues, only Ligue 1 (14 per cent) and the Bundesliga (nine per cent) have given a greater share of minutes to players aged 15-20 than Serie A this season. Granted, the difference between Serie A (5.1 per cent), the Premier League (five per cent), and La Liga (4.3 per cent) is marginal and it’s notably lower than the frontrunners. It is no reason for complacency.

Facts matter. But feelings aren’t wide of the mark, either. In September, Italy coach Genarro Gattuso lamented: “I don’t know how many thousands of oratories (where Italian kids have historically played) have been closed. Kids don’t play in the street for six or seven hours a day like they used to 20 years ago. Parents don’t think they’re safe… these days they play six or seven hours a week, not a day.

“To play football, you also need kit, and kit can cost €500 (£440; $575) a year. That’s expensive. Put it all together, and a lack of talent is normal. We’ve got good players, I repeat, but not enough. They don’t play enough. Kids these days are great at writing because they’re six or seven hours on their iPhone or Samsung instead.”

It’s a theme touched on by Fabregas, too. The Como coach has earned plaudits not only for results but also for the faith he’s shown in youth. Away to Napoli at the weekend, Fabregas was proud to start Jayden Addai (20), Jacobo Ramon (20), Assane Diao (20), Nico Paz (21), Alex Valle (21), and Maximo Perrone (22): two Spaniards, two Argentines, a Senegal international and a Dutchman. None of the kids was Italian.

Cesc Fabregas has promoted youth at Como (Francesco Pecoraro/Getty Images)

“I’ve personally tried,” he said. “The sporting director, who is Italian, has tried to bring as many Italians to the club as possible. I swear to you, I analyse and look out for Italians who can help us raise our game. I have found it incredibly hard — incredibly hard.”

The hope is, one day, in the not-too-distant future, a generation comes through and it gets easier. Until it does, the Golden Boy will continue to be passed between French players like Doue and graduates from La Masia, the Barcelona youth sector that has produced three of the last five winners.