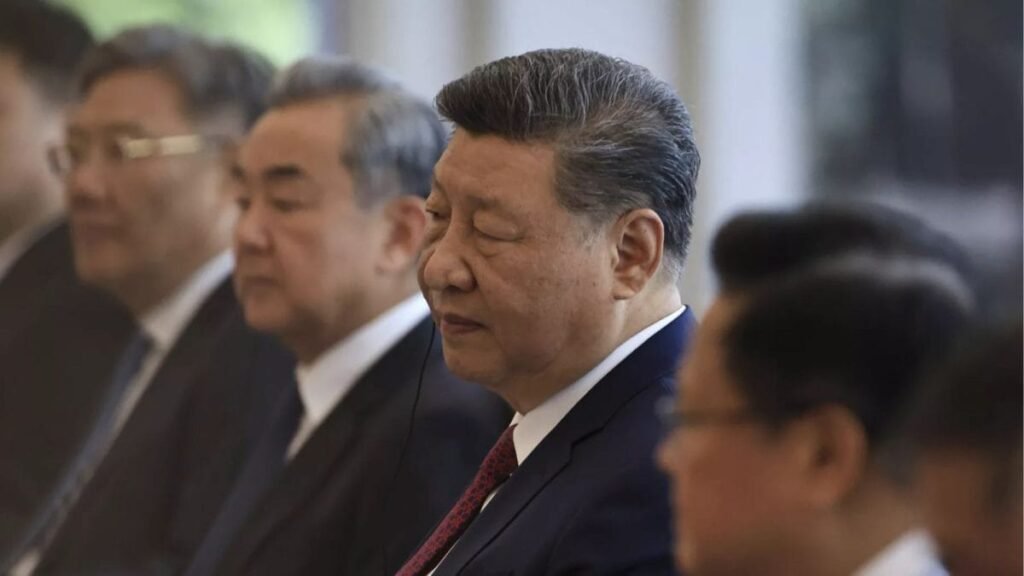

Since he came to power in late 2012, one of Xi Jinping’s core objectives internationally has been to stage a revolution in perceptions of China abroad — notching up victories in what he characterized early in his first term as a global “public opinion struggle” (舆论斗争).

This project, centering on the concept of “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国的故事), responds to what the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership perceives as a detrimental gap with the West of what it terms “discourse power” (话语权). Mainstreaming a hardline notion that emerged in the late 2000s, Xi has set out to resolve China’s historical “third affliction” (三挨) — the contemporary experience of international criticism following earlier periods of military defeat (挨打) and economic poverty (挨饿).

Xi’s vision of returning China — for that is how the Party conceives of history — to its rightful place in global public opinion has evolved beyond traditional national-level state-led messaging to an international communication strategy more actively involving Party-state coordination of voices across locales and administrative levels. It involves leveraging local and regional media and coordinating the production of local multimedia stories through “convergence media centers” (融合媒体中心). It also envisions the participation of businesses, educational institutions and all other aspects of society.

The transformation is happening across the country — with hugely mixed results. In some local areas, the proliferation of the “international communication centers” (国际传播中心), or ICCs, that coordinate much of this work seem a superficial, ineffective and potentially wasteful response to dictates from on high. There are even international branches of local ICCs that are likely to be more window-dressing for the leadership than substantive actions. Take, for example, Hainan province’s recent launch of a Middle East Liaison Center in the United Arab Emirates.

But in more developed media cultures in cities like Shanghai and Guangzhou, the shift could represent a more substantive evolution. It is perhaps too early to say. In Shanghai, the government’s push to remold its “international communication matrix” (国际传播矩阵) — to use a term often favored by state communication planners — resulted in the creation in November 2023 of ShanghaiEye, a multimedia brand under the Shanghai Media Group’s “SMG International Communication Center,” that now claims 3.1 million followers on overseas social media.

ShanghaiEye’s YouTube channel, which currently has more than 400,000 subscribers, runs daily videos covering news and culture. Many of these deal with innocuous issues like tourism, food and culture, but many too echo broader state narratives — about the “real China” (versus the prejudicial Western one, a constant CCP theme); echoing Russian propaganda on Ukraine (and here); and mirroring foreign affairs ministry talking points without reporting or context. Even as accounts like ShanghaiEye, operated by China’s growing network of international communication centers (ICCs) seek to expand their presence on social media channels closed to Chinese users back home, they often cloak or make ambiguous their association with China’s broader external propaganda goals. On Facebook, ShanghaiEye — labeled on YouTube as merely “a multi-platform media brand focusing on high-quality videos” — has no affiliation to the Shanghai CCP leadership mentioned. By contrast, the Facebook account for the government-run China Daily (中国日报) clearly labels it as “state-controlled media.”

Xi Jinping’s new multi-stakeholder approach to what the CCP terms “external propaganda” (外宣) is described by communication scholars in China as a systematic evolution from traditional propaganda to coordinated “narrative innovation” (叙事话语创新) across government, media, business, and social sectors. The ICCs play a key role in this coordination. But ultimately, the approach requires the concerted effort of all.

In an article published online this month, drawing on the insights of several academics, Fudan University doctoral students Liao Xiang (廖翔) and Chen Jingwei (陈经伟) conclude that China’s international communication has moved toward what they term “multi-stakeholder collaborative cross-cultural communication” (跨文化传播的多主体协同). They define three key strategic shifts: 1) coordinated messaging across administrative levels to avoid the “fragmented” approach of previous eras; 2) precision-targeted regional strategies that align local advantages with national objectives; and 3) systematic integration of youth culture and digital platforms to reach “new generation audiences” globally.

The scholars cited in Liao and Chen’s article argue this represents a fundamental departure from traditional state-led messaging, relying primarily on large news wires and broadcasters like Xinhua and CGTN, toward what they describe as a comprehensive ecosystem designed to overcome “cultural discounts” (文化折扣) — the reduced appeal and effectiveness of foreign content due to cultural barriers — that have historically limited China’s ability to project appealing narratives internationally.

All of this might sound inspirational and ground-breaking — just the sort of language state media tends to use to tout Xi’s genius in steering the helm of global communication. But these claims often have a circular quality, citing successes claimed in the manner of self-promotion as evidence of real success.

One of the scholars cited, Chen Zhi (陈智), suggests in his input that the YouTube account of Discover Changsha, an account operated by the Hunan provincial capital’s official ICC, “achieved outstanding results on overseas platforms” with Harry Potter-themed short videos about local culture. This sort of self-magnification is too often found among China’s communication planners, underscoring the yawning gap between lofty ambition and the genuine efforts to understand and engage global audiences. Discover Changsha’s Harry Potter-themed video on the dramatic art of face-changing (变脸) has drawn just 327 views over the past three months.