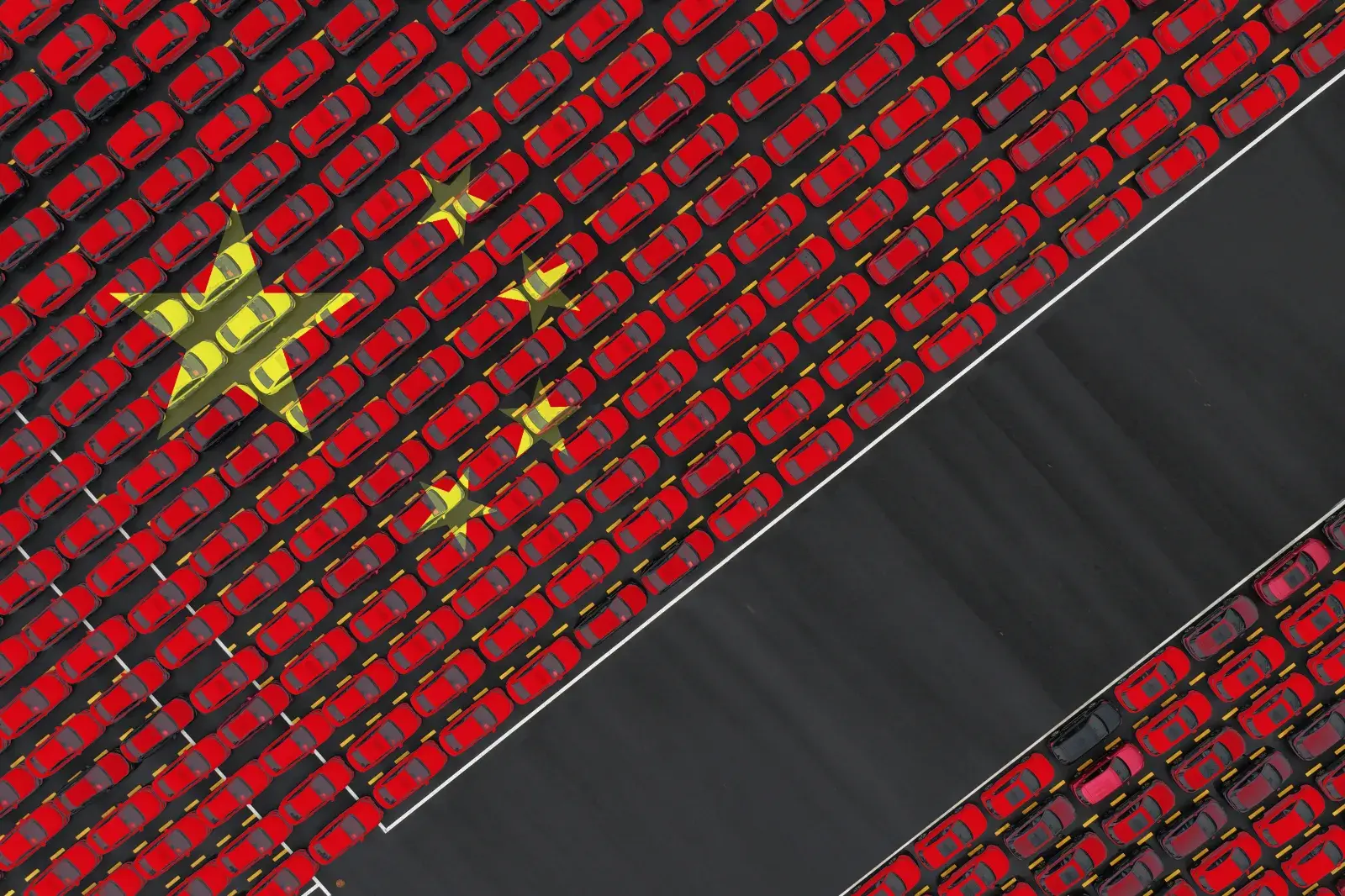

The electric vehicle revolution is often framed as a climate imperative—a way to cut carbon emissions and slow global warming. But the race to electrify automotive fleets is not just about the transportation sector: EVs are the gateway to a new military-industrial era. And China is already winning.

While the U.S. dithers over charging stations and trade restrictions, China has built a vertically integrated EV empire—dominating production, supply chains and the underlying technologies that will define the next century. This isn’t just about cars. It’s about batteries that power everything from smartphones to drones to autonomous weapons. It means building the kind of deep R&D pipelines that can be redirected toward military technologies. It means dominance in AI navigation, robotics and smart cities. It’s about who will control the infrastructure of the future—and who could win future wars.

“A healthy, innovative auto sector drives industrial power far beyond cars,” David Feith, former deputy assistant secretary at the State Department, told Newsweek. “It’s crucial for scale and the downstream flow of innovations.”

Today’s Chinese EVs are computers on wheels, equipped for the digital age with infotainment systems and touchscreens and high-tech features like rotating passenger seats and a weird gimmick that lets cars “dance” or shake to music. Some models even sport a roof-mounted drone that motorists can launch off the car to record video by remote control.

If America fails to lead (or even compete) in the EV space, it won’t just miss its climate targets—it will forfeit its industrial base, hollow out its manufacturing heartland and turn Detroit, once the symbol of American ingenuity, into a legacy domestic supplier of gasoline-powered pickups. In short, the United States stands to lose the technological edge that made it a superpower while the rest of the world zooms past.

“If the U.S. doesn’t invest in new mobility innovations, hundreds of jobs and market share will vanish for good, along with a major shift in wealth,” warned Erik Gordon, a professor at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business.

The EV race is not just a matter of mobility. It’s about sovereignty.

Autos Are an Economic Anchor

China’s bold move into electric vehicles began in 2009 as a top-down policy to compete with foreign automakers, cut air pollution and reduce oil imports. Spurred by subsidies and incentives and its vast industrial production capabilities, China leapfrogged over manufacturing gasoline-powered cars and rocketed to become the world’s largest EV manufacturer with more than 70 percent of global production today, according to the International Energy Agency.

Electric car sales are set to exceed 20 million vehicles worldwide this year; China will make 14 million or two-thirds of them. The next EV leap is expected by 2030, the IEA forecasts, when EVs reach 40 percent of total auto sales globally. But in 2024, EVs were already more than half of autos sold in China and could reach 60 percent this year. By comparison, in the U.S., one in 10 cars sold were EVs in 2024, IEA figures show, and only modest growth is expected this decade.

Even so, the U.S. still depends on its conventional auto industry as an anchor to both economic and geopolitical might. After all, auto factories supplied weapons during World War II and still could. Absent action by American leadership to narrow the EV gap with China by investing in its own competitiveness, China’s scale and velocity in industrial tech and support of EV adoption could cause U.S. automakers to become “increasingly irrelevant,” technology forecaster Paul Saffo told Newsweek.

“If the U.S. doesn’t transition to new energy vehicles quickly,” said auto industry expert Michael Dunne of Dunne Insights, “Detroit will cede the global market and be reduced to a niche supplier of gas-powered pickup trucks and SUVs.”

The hard truth? “We are sitting on an island of ICE [internal combustion engines], rapidly moving back into the 1950s of Detroit with big boomer cars while the rest of the world is moving forward with electric vehicles,” said John Zysman, professor emeritus at UC Berkeley and cofounder and codirector of the Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy.

Sitting Out the EV Revolution

It may be too late to push back the march of Chinese EVs. China’s appealing and cost-competitive electric cars are gaining substantial market share in European markets like the U.K. and France and are up to 85 percent of EV sales in Brazil and nearly two-thirds in Mexico. Such growth is fueled by China’s low labor costs, well-developed component supply chain, fiercely competitive and crowded manufacturing sector and government subsidies, which have combined to lower average EV prices by about 10 percent over the last five years to about $26,000, on par with ICE vehicles.

Rather than trying to keep up, the U.S. is increasingly trying to keep China’s EVs out. This year, the U.S. restricted the import and sale of Chinese internet-connected electric vehicles citing national security concerns, such as spying on drivers, recording images of infrastructure or transmitting data back to Beijing.

The Biden administration announced more than $170 billion worth of investments to foster domestic EV auto production. But now, the outlook for EVs in the U.S. has dimmed due to recent policy shifts under President Donald Trump. The One Big Beautiful Bill eliminated the $7,500 federal tax credit for EVs, and after Trump’s pause on a $5 billion program for states to build out their electric charging station networks was overturned by the courts, the future of the program remains uncertain.

Ineffective policies for the EV market could mirror the loss of the solar energy industry, says Wendy Cutler, senior vice president at the Asia Society Policy Institute, where too-late action left America outpaced and China controlling more than 80 percent of the world’s solar panels.

If the U.S. poorly manages the transition to EVs, it could trigger high unemployment and poverty in Rust Belt and Sun Belt manufacturing hubs. EVs have fewer parts than gasoline engines and automated assembly plants don’t need as many workers. They also don’t need the same workers: EV factory employees need to be proficient in running electrical systems, safely handling high-voltage components and programming and maintaining robots—not exactly Henry Ford’s assembly line operators.

In the 20th century, America’s dominance of the private car industry reshaped its economy, landscape, cities and global influence. The individually owned automobile made possible by Ford’s advances in mass production in the early part of the century unlocked the forces that transformed the country following World War II, including encouraging workforce mobility, fueling suburban expansion, catalyzing the steel and petroleum industries and supercharging consumer culture.

“The leapfrog of the American economy in the past was because of private cars,” Uri Levine, cofounder of Waze, told Newsweek. That dominance didn’t just build wealth—it built geopolitical power.

Today, China is replicating that model with electric vehicles, and the second-order benefits are already cascading: smarter cities, stronger supply chains and a growing lead in AI navigation, robotics and battery technology. If the U.S. fails to keep pace, it won’t just lose the EV market—it will lose the foundation for the next generation of industrial and military innovation. “Now, as U.S. mobility innovations stall, we are starting to get stuck, and that is going to slow us down economically,” Levine warned.

China’s EV Advantage

China’s huge industrial market and modernized infrastructure provide an unparalleled base for its EVs to go mainstream. Chinese EV brands outdo gas-powered vehicles on driving distance and some new models are almost as fast at refueling, with batteries that can be swapped out in under five minutes. This lead is driven by China’s extensive electric charging network, with nearly 10 million charging stations as of May 2025 and growing 56 percent year-on-year, according to the National Development and Reform Commission. This year, Beijing alone plans to build 1,000 ultra-fast charging stations, which can provide 250 miles of driving in a five-minute stop, while the megacity Chongqing is adding 4,000 ultra-fast chargers.

By contrast, the U.S. has approximately 76,000 charging stations, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, with Tesla accounting for 54 percent of fast chargers and building out more supercharger sites with multiple ports, two of them in California.

As China’s climb with EVs continues, this knowhow has spilled over into other next-generation industries. “Over the past 15 years, China has climbed the value chain—starting with electronics then leveraging that expertise to expand and

capture more global production,” Robert D. Atkinson, founder of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation think tank, told Newsweek. “Economists call this cumulative causation: Gains in one sector fuel advances in others. That’s exactly what the Chinese have been doing.”

This domino effect could lead China to leverage its dominance in EVs to yield innovations ahead of the West. For instance, EV maker NIO, boosted by investments from Chinese province Anhui, developed battery-swapping stations to exchange depleted batteries for recharged ones within minutes. Modeled on mobile data plans, subscription plans for battery-as-a-service for leased EV batteries have sprung up in China.

In the electrified city of the future, parking spaces could be converted into lots for ridesharing and robotaxis, supercharging stations and dedicated bike lanes, said Kara Kockelman, professor of transportation engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. Increased adoption of EVs leads to more autonomous driving shuttles, better urban planning, reduced traffic congestion and less air pollution. This future is already arriving in digitized cities like Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen.

Thanks to China’s favorable governmental policies, scale and a robust infrastructure, compared with a fragmented regulatory and hesitant approach in the U.S., China stands to also gain a competitive advantage in the autonomous vehicle market and the AI navigation capabilities to power it, said John Helveston, an associate professor at George Washington University’s engineering management department.

Baidu’s Apollo Go, a Chinese autonomous driving leader, has rolled out robotaxi services across many Chinese cities, far ahead of the progress of Alphabet’s Waymo, the primary player in the U.S., while General Motors canceled its money-losing Cruise robotaxi service in 2024. Tesla is still in the early stages of testing. “Five years from now, I’d bet on a Chinese company figuring out how to make a fully autonomous car that can out-compete even Waymo today because there’s this industrial ecosystem all around it,” Helveston predicted.

Whatever the future standards are for EVs, it will be the market leader who sets them. This is already playing out with the technical charging standards for electric plugs. Currently, the North American standard is modeled on the Tesla charge post, which GM, Ford, Rivian and other U.S. automakers have adopted. Europe requires a different standard for fast charging. China has its own ultra-fast system, which Tesla relies on for the Chinese market. Meanwhile, a new high-power plug with a lightweight, smaller connector design, called ChaoJi, is being tested in China and Japan.

China’s vast EV market and extended supply chain network provides the additional benefit of vertical integration. Chinese EV leader BYD, for example, has streamlined operations by bringing parts for assembly under one factory roof, which can improve quality control and speed up R&D cycles. BYD even owns a shipping fleet of six vessels which can each carry 9,200 vehicles, providing better control of the timing and costs of its distribution routes. It’s been a generation—36 years—since Ford operated a shipping fleet, and that was for transporting iron and coal across the Great Lakes to Dearborn, Michigan.

Another advantage for China in this new EV age: It is technology entrepreneurs, not incumbent automakers, who are leading the industry’s disruptive changes. EV makers like Xiaomi (which first made smartphones), XPENG and NIO began as tech startups during China’s internet boom of the 2010s. Supported by leading private equity investors from China and the West, they raised large amounts of capital, went public on Hong Kong and New York exchanges and carved out strong leads in China.

By contrast, GM and Ford have joint ventures with Chinese partners that are often state-owned enterprises established some 25 years ago, and today, are experiencing shrinking influence and market shares.

Defense Supremacy

A pressing issue in the realm of EVs is dual-use technologies for commercial and military purposes. “Military-civil fusion has exploded in recent years with the evolution of technology,” national security expert Feith explained, and advances in commercial sectors can feed directly into defense capabilities. Leadership in batteries, robotics and automation brings economies of scale and deep R&D pipelines that can be redirected toward military use.

“Today, the United States is increasingly reliant on foreign adversaries for the minerals, technologies and supply chains that will drive economic growth, enhance energy security and strengthen the national defense,” retired Admiral Jonathan Greenert, co-chair of SAFE’s Energy Security Leadership Council, wrote in a recent report, “The Pillars of Power.”

“The stakes could not be higher. The decisions made today will determine whether the United States reasserts and secures its position as the world’s leading economic and technological power or continues to cede ground in industries critical to its future,” he concluded, urging coordinated action to restore America’s industrial base, secure critical supply chains, modernize the electric gird and strengthen national defense through energy and technological leadership to avoid future trade and tech conflicts reminiscent of Middle East regimes’ leverage over oil.

China has gained a lead in batteries and is aiming for dominance in robotics and next-generation AI-powered manufacturing. The battlefield applications of these fields are already being demonstrated. Drones equipped with advanced batteries and sensors can fly longer, avoid obstacles and maneuver into swarm tactics that can win battles, such as with Ukraine’s recent coordinated, long-range drone attack into Russia known as “Spider Web.”

EV self-driving systems can be adapted for military use to autonomously guide unmanned tanks, transport supplies and patrol areas. Efficient, high-torque electric motors can be repurposed for precise navigation and dexterity for military strikes. Sensors and AI technologies used in connected passenger vehicles can be transferred to use in warfare to improve battlefield monitoring and navigation of military equipment.

The batteries that power next-generation military technologies—drones, humanoid robots, AI navigation—are at the heart of the U.S.-China competition for industrial and technological leadership. Drones and batteries are currently dominated by giant Chinese tech companies: Shenzhen-based drone maker DJI, privately held and largely owned by its billionaire founder Frank Wang, and Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited, or CATL, an EV-focused battery spinoff of the Japanese electronics giant TDK founded by Robin Zeng.

U.S. fears that DJI drones could beam sensitive images back to China previously led to a ban on their use in the U.S. military. The Commerce Department has choked off its supply of U.S. chips and sensors, and the Treasury has blacklisted the firm from American investment. And yet, DJI accounts for 70 percent of global drone sales.

Located in Fujian province, CATL is the world’s largest maker of lithium-ion batteries and supplies Tesla and Volkswagen in China. CATL claims roughly half of China’s battery market and more than one-third worldwide, and it’s now pushing into the U.S., raising concerns about a Chinese supplier that can power everything from EVs to defense systems.

Achieving cost parity with China for batteries requires production at scale, and that scale depends on strong, sustained demand for EVs, the largest battery consumer. Without it, the U.S. risks relying heavily on China for the very power source that underpins future technologies critical to national security and defense. “This would mean deep reliance on, and vulnerability to, China,” said Dunne.

CATL recently struck a licensing deal with Ford to supply battery technology for a new $3.5 billion Ford-owned plant in Michigan. The move quickly drew scrutiny from the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, which questioned Ford’s reliance on Chinese technology, minerals and workers. CATL’s U.S. ambitions face another hurdle: In January, the Pentagon blacklisted the company over alleged ties to China’s military—a charge CATL denies.

China’s dominance in electric vehicles is also boosting its robotics sector. While the U.S. has achieved an early lead in robotics innovation, it lags in large-scale production with no U.S. firm currently mass-producing industrial robots. Meanwhile China, which has widely deployed robotics in its vast manufacturing sector, announced a $138 billion investment in robotics and AI under its Made in China 2025 policy aiming to close the technical gap and establish itself as a global leader in advanced manufacturing.

Ultimately, America’s culture of innovation is a decisive advantage that China has struggled to replicate. Chinese engineers excel at copying and refining Western advances, but true disruptive invention remains harder to come by. Beijing is catching up, as shown by the sudden rise of AI startup DeepSeek.

In this massive auto industry shift, GM and Ford vehicles are holding on to global market shares of about 9 percent and 6 percent. Quite the change from the 1960s, when the Big Three automakers dominated and China made hardly any cars. Today in China, American-made gas-powered models—a source of profits and access to suppliers for U.S. automakers—are quickly being sidelined in the world’s fastest-growing EV market. In 2024, GM sales in China dropped 14 percent and, for the first nine months of the year, its market share there declined from 8.6 percent to 6.8 percent, down from 15 percent in the mid-2010s. In the first six months of 2025, the automaker posted a rebound, with sales rising 9.4 percent, boosted by momentum in its new energy vehicles.

Down But Not Out

However, a shake-out is coming in China’s dynamic EV market. More than 100 brands currently compete with one another, leading to steep discounts and price wars. Only 15 Chinese EV makers are expected to emerge from this boom, predicts consultancy AlixPartners.

Not surrendering, in the U.S., GM and Ford have pledged upward of $90 billion to build battery plants and convert old factories that will begin operating within three to five years—a long time in the fast-moving EV market. The Detroit automakers have enjoyed some notable EV wins in pickups (F-150 and Silverado) and SUVs (Equinox and Mustang Mach EV). Tesla has been in a sales slump this year but still claims about half of EV sales in the U.S.

And don’t count out America’s world-leading culture of innovation. Two San Diego-based firms, South 8 Technologies and UNIGRID, have each landed $12 million in strategic funding and dozens of patents for longer-lasting, faster-charging battery technologies that could accelerate the adoption of EVs.

Tesla had a first-mover advantage in China in 2013, leveraging the government’s support of EVs with subsidies and incentives and its production base and opening a gigafactory in Shanghai in 2019. China became Tesla’s number one market in sales and its biggest production and export hub.

Tesla is still regarded by the Chinese as a premium brand, and its Model 3, at around $33,000, is pricier than comparable Chinese makes such as the Xiaomi SU7 sedan at $30,400. But Tesla has recently been discounting in the highly competitive Chinese market as well. And its prestige image started to fade as snazzy new Chinese EV makers emerged and Tesla’s lineup needed a refresher (a new, roomier six-seater Model Y had a successful launch in August).

While chalking up 8.8 percent growth last year, Tesla’s share of the Chinese market fell to 6 percent down from 15 percent in 2020. Moreover BYD, which Warren Buffett had backed in 2008, surpassed Tesla as the top global EV seller in 2024 and keeps widening its sales lead.

“The Chinese EV makers are advanced and are innovating at the cutting edge, and Tesla needs to be able to keep up with that,” said China and tech policy expert Paul Triolo, a partner at the Washington, D.C.-based business advisory firm DGA Group. “China has an advantage because they have the supply chain for EVs, particularly rare earth minerals and batteries—and a big advantage in costs.”

There are still plenty of unknowns about the progression of EV technology. Other disruptive technologies of the future could dent their incline. “It’s quixotic to believe that electric will be the model of all vehicles,” said tech futurist George Gilder, adding that he foresees “a strong role for emerging renewable energy, hydrogen-powered vehicles.”

However, the second-order impacts of a global automotive realignment are already playing out. Shortages of rare earth minerals idled Detroit production lines earlier this year and only eased after the U.S. made a deal with China to lift export restrictions of certain chip design software. To avoid further supply line pinches like this, GM recently struck a long-term deal with Noveon Magnetics, whose San Marcos, Texas, facility is the only rare earth magnet manufacturer in the United States.

Over the past two decades, China has risen from imitator to innovator, advancing rapidly in new energy, robotics, batteries and drones—and related military power. “We can’t block China from technology,” Jim McGregor, chairman of APCO Worldwide, Greater China, told Newsweek. “We can slow them down a bit, but we need to figure out how to get along and de-risk it.”

Photo-Illustration Justin Metz for Newsweek