Dominic CascianiHome and Legal Correspondent

PA Media

PA MediaThe director of public prosecutions has said the China spy case collapsed because a top national security official could not say the country had been classed as an “enemy” when the Conservatives were in power.

In a letter to MPs, Stephen Parkinson said the unwillingness of Deputy National Security Adviser Matt Collins to say that China had been an active threat to national security between 2021 and 2023 was “fatal to the case”.

Parkinson has been under pressure to explain why two men were charged with spying only for the case against them to collapse 16 months later without going to trial.

A political blame game erupted over the case – but the focus has now switched to the role of officials. And government witnesses are expected to query some of the DPP’s written evidence when they appear before the parliamentary committee next week.

In April 2024, Christopher Cash and Christopher Berry were charged under the Official Secrets Act 1911 over allegations that they had passed information to a Chinese intelligence agent.

They were cleared of all wrongdoing in September after the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) withdrew its case. Both men always denied wrongdoing.

After weeks of pressure, Parkinson, who is the head of the CPS and director of public prosecutions, has now written a long letter to the national security strategy committee, ahead of appearing before it on Monday.

It sets out his account why Mr Cash and Mr Berry were first charged – and how the case then unravelled.

The men were first arrested in March 2023 on suspicion of offences under the Official Secrets Act – and if the case were to go before a jury, the prosecution would have to prove that the defendants had carried out activity “prejudicial to the safety or interests of the State”.

Secondly, a jury would also have to be sure that the UK government had considered between 2021 and 2023 – when the alleged offending occurred – that China was an “enemy”.

Prosecutors concluded that they would need to show a jury that China was an “enemy” with the help of expert factual evidence from Matt Collins, the Deputy National Security Adviser (DNSA).

As DNSA, Mr Collins is responsible for coming up with an assessment of threats to the UK’s national security.

He began drafting, with advice from his own lawyers and other officials, a statement which had to be solely focused on the then Conservative government’s official and publicly disclosable conclusions about the threat, if any, that China posed.

This evidence is separate from any information generated by the intelligence services that remains secret.

The eventual statement went into detail about the activities of Chinese intelligence agencies and how they seek to obtain information about the UK’s political workings – but the word “enemy” was removed by the time a final version was completed in December 2023 and shared with Downing Street.

Mr Collins, in his own letter to MPs, said he told police investigating the case he could not call China an “enemy” as this “did not reflect government policy”.

In July 2024, a Court of Appeal ruling on the legal definition of enemy, in a separate case concerning Russian interference in the UK, set off alarm bells in the CPS.

It underlined the need to provide a jury with a factual account of why a state could be considered an enemy under the Official Secrets Act – and while the government had provided a clear conclusion about Russia, it had not done so for China.

In his letter to MPs, Parkinson said that ruling meant the CPS and police had to go back to the DNSA to ask him for more evidence about China.

That evidence was essential because prosecutors knew that the defendant’s barristers would question whether there was no evidence at all that the UK had regarded China overall as a threat between 2021 and 2023.

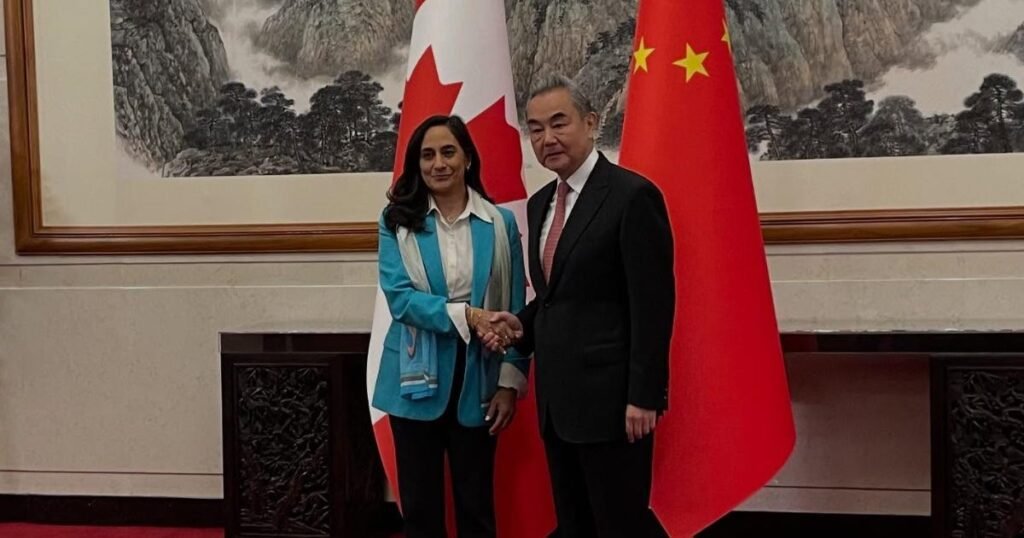

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesIn July, the Director of Public Prosecution’s team told the Cabinet Office: “To prove the offence, the jury would need to be satisfied so that they were sure that, at the material time, China was an enemy.

“That China was an active espionage threat would not be sufficient without examples which adequately demonstrate the nature and extent of the threat, such as to ground a finding that China was an enemy.”

That led to two crunch meetings – which led to the case’s collapse.

At the first meeting on 14 August, Mr Collins told the prosecution team that “he would not state in evidence, if asked, that China posed a risk to our national security at the material time, either in open Court or in a private session.

“He would also not accept that China was opposed or hostile to the interests of the United Kingdom at the material time,” says Mr Parkinson’s letter.

“He would accept, if asked [at trial], that China was not an enemy in the ordinary meaning of the word, and would not answer the question, if asked, whether China is an enemy within the meaning of the Official Secrets Act. He would say that is a matter for the jury.”

House of Lords

House of LordsBy a meeting on 9 September this year, Mr Collins had been told that without such evidence, the case would collapse.

Mr Parkinson’s letter tells MPs the official reiterated he could not provide the evidence they sought because it would not reflect the former government’s position.

“In the conference, the DNSA [Mr Collins] confirmed to counsel that, in relation to the 2021-2023 situation, he would not say that China was an active threat.

“Successive governments had declined to categorise it as such.”

Mr Parkinson tells the MPs that given the defence teams knew what Mr Collins had said in his statements, prosecutors were under a duty to call him to give evidence at a trial – and he would be cross-examined.

The CPS could not go to the DNSA and then, on discovering he could not provide the facts prosecutors needed, choose an alternative witness.

[The DNSA’s] unwillingness to say that at the material time China was an active threat to national security was fatal to the case,” said Mr Parkinson.