Key Takeaways

- App store age verification bills like the federal App Store Accountability Act (HR 3149 / S. 1586) are emblematic of public support for age verification in the sense of “rules for thee but not for me” – public willingness to provide facial scans or government issued ID to access apps is consistently low.

- Facial scan-based age estimation is error prone, particularly for teenagers, and it is more than plausible that a majority of teens and many adults near age thresholds would be classified into the incorrect age category under these bills, with a mix of both over-estimation and under-estimation errors.

- A 60% majority of teens in the relevant age category 15-19 lack drivers’ licenses and a large number have no government-issued photo ID.

- Up to 11% of adults lack non-expired, government-issued photo ID that would satisfy age-verification mandates.

- Requiring app store age verification will create a data breach target for bad actors seeking sensitive biometric and ID information.

Lawmakers in several states and in Congress have proposed bills similar to Utah’s App Store Accountability Act that force app stores to verify every user’s age and to prevent minors from downloading apps without parental consent. In particular, Utah’s statute requires app stores to “request age information” at account creation and “verify the individual’s age category using commercially available methods that are reasonably designed to ensure accuracy.” The federal App Store Accountability Act bills in the 119th Congress copy much of the Utah statute’s language, including provisions that require “age rating” for all apps, force app developers to notify stores of almost any change to the features, functions, and user experience of their apps, and make violations liable for damages and penalties under the unfair and deceptive trade practices laws.

In practice, these approaches are poised to fail. Public support for age checks or age verification in the abstract evaporates when people are actually asked to upload IDs or submit to face scans; data shows that voters and consumers only support age verification “rules for thee but not for me.” Even in the event that users are willing to submit to face scans, face-based age estimation is notably error-prone, and this is especially true for teens around legal age cutoffs relevant to these bills for two of the methodologies tested. For example, minors in the UK have been using images of video game characters’ faces to evade UK age verification requirements.

This means that both false positives and false negatives will be a major issue, with underage minors accessing content they aren’t supposed to while teens and adults above relevant age thresholds find themselves locked out of apps they should have access to. The alternative, providing a government-issued ID, runs into the serious problem that teens—and even many adults—lack the IDs these bills assume. Moreover, the mass collection of sensitive documents and biometrics creates a very tempting sensitive data target for bad actors and creates a huge centralized data breach risk.

“Sure, verify ages” only applies until the voter has to hand over an ID or a face scan to access apps

Polling consistently shows that broad support in principle for protecting kids online is not the same as willingness to upload ID documents or faces to get into apps:

- In a nationally fielded survey, two-thirds of Americans said they are not comfortable sharing their own government ID with social media companies to verify age, and 70% are not comfortable sharing their child’s ID.

- In the U.K., where comparable rules are rolling out under the Online Safety Act, Ipsos finds that while people back age checks in principle, willingness to actually provide proof plummets for common services: only 19% would provide proof of age for dating apps; 37% would do so for social media; 38% would for messaging apps.

If most users refuse to upload IDs or submit to biometric scanning, app stores face mass lockouts, which undercut the law’s stated goals. Moreover, users will face a government-mandated choice between providing a facial scan or government ID with concomitant exposure to privacy concerns and data breach risk, or losing access to apps that are important to First Amendment-protected activities like accessing information, communicating, and expressing themselves online.

Face-scan “age assurance” is not accurate enough to identify teenage thresholds

NIST’s 2024 Face Analysis Technology Evaluation (FATE) provides the most authoritative test of face scans for age estimation and verification to date. FATE reports best-case mean absolute error (MAE) around 3.1 years on visa-quality photos, a mean absolute error wider than both the “child” or “teenager” age categories in the App Store Accountability Act. Accuracy varies by algorithm, dataset, sex, image quality, and age itself.

Crucially for policy:

- For 18- to 24-year-olds, reported MAEs around 3–5 years are common depending on dataset/algorithm. That is too imprecise near 13/16/18 age cutoffs, and creates enormous room for adults to be misclassified as a teenager or even a child under the App Store Accountability Act, losing access to apps.

- One-year age estimation accuracy is incredibly low for 13 year olds: across methodologies, just 7.2% to 34.5% of 13 year olds were correctly estimated within one year of their actual age. Note that being estimated one year younger can cause loss of access to all apps.

- Similarly, one-year age estimation accuracy is very low for 17 year olds: across methodologies, just 4.7% to 30.3% of 17 year olds were correctly estimated within one year of their actual age. Note that being estimated one year older can cause access to adult content.

- Three-year age estimation accuracy is far too low for 18 year olds: across methodologies, just 33% to 62% of 18 year olds were correctly estimated within three years of their actual age. Note that being estimated just one year too low can cause a loss of access to all apps without parental consent for a legal adult.

- NIST directly measures teen misclassification risk: for 14–17 year-olds, false-positive rates for being classified ≥25 can range up to 28% depending on sex, data type, and vendor—plus MAEs up to 6.3 years.

That combination guarantees significant Type I (under-blocking minors who should be blocked) and Type II (over-blocking adults who should pass) errors in real-world app flows with mixed photo quality (selfies, webcams, dim rooms). Even NIST cautions performance is sensitive to image quality and demographics—conditions app stores cannot control, and users cannot always control. Combined with expansive liability potential in most age-verification proposals, covered platforms will unnecessarily limit access for large swaths of lawful users, creating a race to the bottom.

Many teens and adults don’t have the IDs these bills require

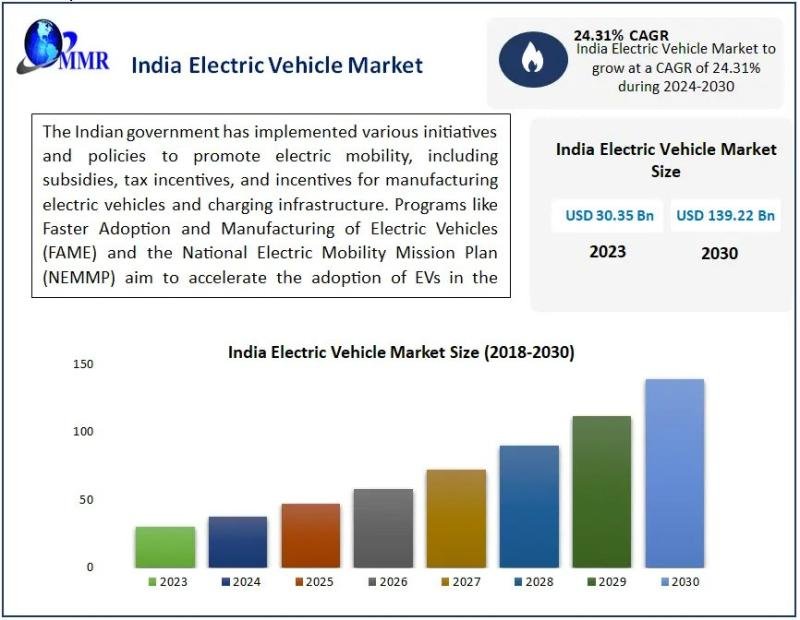

Teens: U.S. licensure among teens has fallen for decades. Best-available aggregates show only about 25% of 16-year-olds (down from about half in 1983) and 60% of 18-year-olds had a driver’s license in recent years; across the 15–19 age range, just 40% hold licenses.

Adults: Using the 2020 American National Election Studies (ANES), researchers estimate 11% of adult U.S. citizens (about 25 million people) lacked non-expired, government-issued photo ID suitable for strict ID rules; about 12% lacked a current driver’s license, and ~3% lacked any non-expired photo. Young adults are disproportionately without ID (e.g., 15% of 18–19-year-olds lacked any photo ID).

Passports are far from universal: official data show roughly 160–170 million valid passports in circulation (between 45–50% of Americans), with some states below 25% possession.

Up to 60% of U.S. teens between 15-19 cannot present an acceptable ID, and the fraction is likely significantly higher for teens under 16. Between 3% and 12% of all U.S. adults, and about 15% of 18-19 year old adults, cannot present an acceptable ID. Requiring ID to access app stores means locking out millions of lawful users—or forcing costly, slow, and inequitable workarounds.

The very act of collecting so much personally identifiable information creates data breach risk

While the app store age verification bills typically include some data protection provisions, such provisions are insufficient to outweigh the risk created by collecting such sensitive information at scale. For example, the federal App Store Accountability Act bill would require an app store provider to “limit[] its collection, processing, and storage to what is strictly necessary to verify a user’s age, obtain verifiable parental consent, or maintain compliance records” and “adopt[] reasonable administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to secure the collection, processing, storage, and transmission of this data, including through industry-standard encryption”—in other words, collect only the needed information (e.g., face scan biometrics, pictures of government-issues identification documents) and protect that information using standard industry practices.

Unfortunately, standard industry practices are not foolproof, which explains why most digital services do not want to collect such sensitive personally identifiable information. The act of collecting passports, driver’s licenses, and face scans creates a high-value target. Recent incidents illustrate the risk:

- Tea, a women’s dating-safety app that required a selfie with government ID, suffered a breach in July 2025 that exposed about 72,000 images, including about 13,000 selfies and photo IDs, many later posted to 4chan.

- Discord disclosed a breach at a third-party support vendor that exposed some users’ government ID images used for age confirmation, despite retention/deletion policies.

These incidents are not outliers; they show how verification flows expand the attack surface far beyond core app data by forcing the collection of personally identifiable information. The more jurisdictions mandate IDs/faces at the gate, the more such caches exist to be misconfigured, scraped, or extorted. All it takes is one error with an update, and hundreds of millions of individuals’ most sensitive personally identifiable information would be at risk.

Real-world rollout evidence: heavy friction and easy circumvention

The U.K.’s new enforcement of “robust” age checks has produced exactly what critics predicted: millions of checks per day and a surge in VPN usage to bypass them. Within days of enforcement, VPNs topped the App Store charts and providers reported 1,800%+ spikes in downloads.

Harsher gates don’t neatly separate minors from adults; they often block or burden many legitimate users while savvy teens route around them.

Why “commercially available” methods still won’t save these bills

Both Utah’s law and the federal draft require “commercially available” age-verification methods. In practice, that means ID matching, face-based age estimation, or credit/financial checks—each with the weaknesses above.

- IDs exclude millions of lawful users (60% of teens, 15% of 18-19 year olds, and between 3%-12% of all adults) without accepted photo ID.

- Face scans often have 3–6 year average age estimation errors in the very age bands relevant to the age thresholds in these laws, with measurable false-positive rates that would routinely misclassify teens.

- Credit or financial proxies (credit cards or banking accounts) further disadvantage unbanked or under-documented populations, still require sensitive data sharing, and would not work for most teens (only 19% of 13-17 year olds have access to a credit card), or a large fraction of adults near the age 18 threshold (more than half of college students from low income families (52%) and of those aged 18-20 (57%) do not have a credit card).

No commercially available method would avoid either enormous age category misclassification risk or denying all app access to a large fraction of teens and adults.

The bottom line

Age-verification laws for app stores will likely be political landmines. They generate headlines and polling sound bites before implementation, but once implemented they collide with human behavior and technical reality in ways that users hate:

- People won’t want to upload IDs or faces. No one enjoys facing a “papers, please” requirement to check their messages from friends.

- Face-age estimation misfires right where it matters (teens), producing inevitable Type I/II errors around age thresholds in the bills.

- Millions of teens (and many adults) don’t have acceptable IDs.

- Building new troves of IDs and biometrics invites data breaches—and we already see them.

- Early rollouts abroad show friction for legitimate users and workarounds for determined teens.

Policymakers should pivot from universal ID checks to risk-proportionate approaches that minimize sensitive data collection: device-level parental tools, privacy-preserving age-range attestations, and targeted enforcement against bad-actors, as these measures are more likely to work without turning app stores into nationwide ID checkpoints.